All fears eventually lead to abhinivesha – the fear of death and the will to continue to exist. This is considered one of the five kleshas, or obstacles to attaining the state of yoga. The eight limbs of yoga are designed to eradicate the obstacles to this union with the eternal and entering nonduality.

Anxiety, one of the most-commonly reported mental health disorders in the general community, is the body’s natural response to stress. It is the mobilization of metabolic energy towards necessary action, dominated by the autonomic nervous system’s sympathetic response – the body’s innate accelerator. Chronic anxiety is the inability of the autonomic nervous system to flow between sympathetic arousal and parasympathetic calm. A conditioned feedback loop has been established that keeps the system in chronic activation.

When the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is activated, our heart rate and respiration accelerate, blood flow moves from the skin and visceral organs to muscles in the extremities, and pupils dilate to take in more of the environment. Under threat, this part of the nervous system is responsible for activating fight and flight responses necessary for survival. Under normal conditions, when there is no threat to life, it makes energy available so we can stay alert and meet the demands of daily life, engage in recreation and vigorous play or exercise, and for sexual activity.

In a nervous system that is operating optimally, if sympathetic activity reaches a certain threshold, the parasympathetic nervous system (PPNS) response engages, slowing things down and returning blood flow to the viscera to support digestion and organ function. This intrinsic balance creates heart rate variability (HRV), a measure of the variability in the heartbeat in relationship to the breath (on inhale, heart rate increases, on exhale, heart rate decreases). High HRV is associated with better physical and mental health. Low HRV is the opposite—a marker of poor health and mental health.

In anxiety disorders – from generalized anxiety to panic disorders to posttraumatic stress or PTSD – the nervous system has lost this reciprocal relationship between SNS and PPNS and has become sympathetic dominant. It is as if a car’s engine was constantly revving, burning up fuel unnecessarily, and eventually overheating and melting down the system. The associated constriction in the blood vessels creates tension in the body and in the mind, and eventually generates inflammation and impairs immune function. A chronic cascade of stress hormones activated by the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal axis further creates endocrine disturbances.

On a psychological level, this physiological state sends warning signals to the brain, which through a process coined “neuroception,” begins to interpret danger and threat – even when there is none. The body is responding to a scary movie playing on the screen of your mind, replaying the painful past or anticipating disaster in a yet-to-occur future.

This vicious loop of hypervigilance and hyperarousal generate distorted or intrusive thoughts or images, emotions of intense fear, anger, and mistrust, further impairing our self-perception and our ability to relate to others and seek support and regulation in social engagement. It is important to note that these are automatic responses that have been conditioned by overwhelming life experiences. Over time, the responses – a panic attack or “flashbacks,” for example – become disconnected from their origin creating a sense of helplessness. Yoga’s self-study and witnessing practices help us gradually uncover the patterns so we can have the choice to change them.

Eventually, because of the body’s innate intelligence, the system will shut down all activity by engaging in a high parasympathetic response leading to immobility, numbness, dissociation, lethargy, apathy, impaired digestion, pain, and other symptoms we have come to equate with depression (more on this in the next installment focusing on depression). Chronic stress can enhance susceptibility to inflammation. Increases in inflammatory markers, such as CRP and IL-6, are associated with decreased parasympathetic nervous activity and are reflected in low HRV. In extreme cases, some people may develop autoimmune disorders or medical syndromes.

The experience of anxiety, as with every other human experience, may be different in each individual and uniquely sourced in their embodied lived experience. In other words, anything from early experiences of trauma (including pre-natal experiences and the ancestral trauma of oppression) to the chronic stress of living in a world that does not value rest and overvalues performance and achievement, can create this internal demand for SNS energy that is not needed in the present moment.

Include in this category are the stress and trauma of living in a culture of patriarchy and white male supremacy. Socio-economic status, class, gender identification, and racial or ethnic background all impact how safe or unsafe we feel in the world because of systems that privilege some and marginalize others. If you are a woman, person of color, gender non-conforming, differently-abled, or not neurotypical, chronic anxiety might be a more common experience. There are significantly more stressors to which the nervous system must respond, explicitly or implicitly, if you live in these intersections. Undoubtedly, socioeconomic stressors, cultural definitions of health and illness, lack of social support, and the general social environment influence the stress load. These disparities were made abundantly clear by the COVID pandemic in the way it affected people of color.

Yoga also explains that we experience fear because we are disconnected from our eternal essential nature, and therefore fear that we will lose our existence if we die. All fears eventually lead to abhinivesha – the fear of death and the will to continue to exist. This is considered one of the five kleshas, or obstacles to attaining the state of yoga. The eight limbs of yoga are designed to eradicate the obstacles to this union with the eternal and entering nonduality. In yoga philosophy, anxiety also would be considered an excess of rajas, one of the primordial forces of creation responsible for activity. So, let us see what yoga offers as solutions to anxiety.

1. The yamas invite us to approach life with honesty, generosity, non-stealing, moderation, non-attachment, and an attitude of non-harming. As we make a lifestyle choice to live by these principles, we might begin by lowering the high demands of perfectionism, by being truthful about our limitations, and by eliminating harmful negative self-judgments. We can moderate stimulants, whether caffeine or drugs, as well as excessive negative mental stimulation that robs us of peace.

2. The niyamas teach us to engage in self-study, to investigate what is helpful and unhelpful in our quest to reduce internal suffering. They also teach us to surrender to a higher spiritual force which can be both a source of strength as well as nourishment. The niyama of santosha, or contentment, teaches us to cultivate this quality of appreciation for the simplest of things, like our breath. We begin to think of the wellbeing of others and not just ourselves, invigorating selfless action.

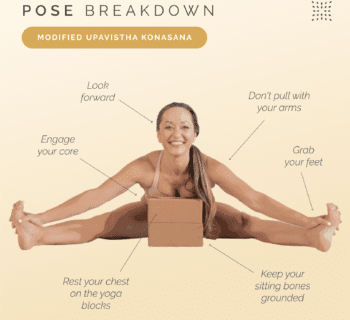

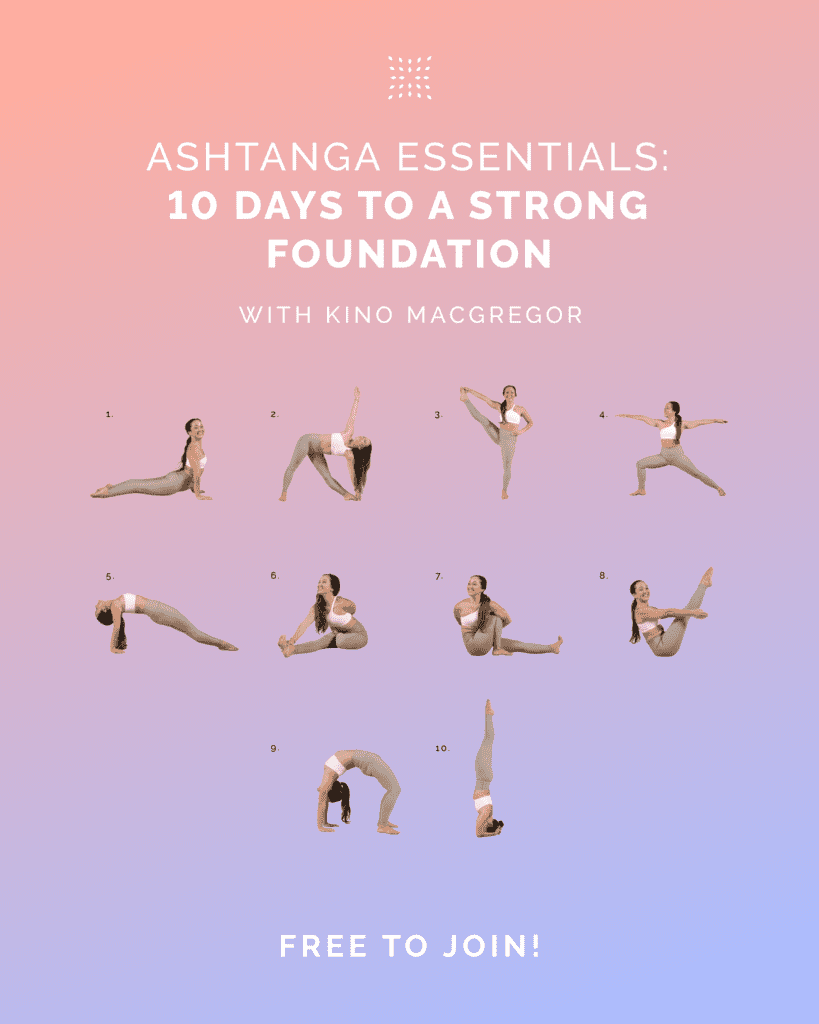

3. Western yoga has become synonymous with asana or physical postures. Asana categories that can help reduce anxiety/rajas include extensions, forward bends, twists, inversions, and backbends on the abdomen – with the goal of purifying the body and igniting the digestive powers that will help us process metabolic energy and psychic disturbances. Perform these poses by slowing down the movements and finding stillness and stability, anchoring the mind in the present moment. Mulabandha and uddyana bandha or the pelvic and abdominal locks can help us get grounded and centered. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali specify that the perfection of the pose is accomplished when we find sthiram and sukham, stability and ease. It is not about excessive effort and wasting precious energy or prana. Then we can contemplate the infinite and move beyond our limited sense of self. The most important asanas are the seated meditation poses when the soul and the mind take a seat in the body.

4. Pranayama, the expansion of prana by cultivating sensitivity to the subtle breath, can also help us anchor the mind so it is not scattered. Where mind goes, energy flows. Ujjai breath with focus in the throat can stabilize mind and prana. Sama vritti, equal inhale and exhale can center us and increase HRV. Longer exhales further engage the calming parasympathetic response. Alternate nostril breathing or nadi shodhana will further increase a sense of balance by bringing the right and left hemispheres of the brain into equanimity.

5. Pratyahara – or the withdrawal of the senses, begins to draw the restless mind away from the external world, the past or the future (which only live in our imagination) and brings it into the present moment. This can be accomplished throughout the practice of asana by coordinating the attention of the mind with the movement of the body and the cycle of the breath. Or it can be further enhanced in a long restful savasana or yoga nidra practice.

6. Samyama encompasses the remaining three limbs of yoga: prana dharana, dhyana and samadhi. These three steps are what we would consider as meditation. Meditation, according to sage Patanjili, is the step that dissolves the obstacles, eliminates suffering, invites transformation, and introduces us to the eternal light of our inner teacher, Ishvara, a special Purusha, the primordial source of all spiritual traditions and of all creation, pure Consciousness. It is therefore the most important, albeit the least utilized of all the limbs of yoga. Dharana is the concentration of prana in a particular location, maybe with a particular mantra or Sanskrit sound. Dhyana is the penultimate state when mind merges or dissolves in the light of prana and the sound of mantra, entering an abiding sense of calm. These steps then lead to the final step of Samadhi, where observer, the object of observation, and the act of observing merge. Samadhi is more the by-product of the previous steps than a step itself. How samyama can help with mental distress is that it progressively helps us identify with Purusha/Ishvara, the observer of experience, the witness – creating a distance between the distress of anxiety in all its forms (sensations, emotions, thoughts, and images), and our real or essential self that is untouched by experience. Again, sage Patanjali states that when Purusha is established, we cease to be affected by the world of duality. Over time, we are more identified with Awareness, the Witness of experience, and less identified with our likes and dislikes, our limited self-perception, our past traumas, or our future fears. This distance gives us the choice to move awareness to the present moment and toward more helpful thoughts, feelings, and behaviors—thereby increasing self-control and reducing impulsivity and compulsivity.

Modern neuroscience research is beginning to quantify the benefits of yoga and has identified that even short interventions of moderate yoga practice:

a) increase the production of GABA in the brain, an inhibitory neurotransmitter that induces calm.

b) Increase heart-rate variability (HRV) by re-patterning the breath from rapid and shallow to smooth, un-interrupted and even.

c) Increase vagal tone, a measure of health in the PPNS response.

d) Reduced activation of the HPA axis.

According to reviews of the research, if yoga does produce an anxiolytic and antidepressant effect, the exact causal mechanism is likely to be complex, affecting multiple body systems. Yoga may best be delivered as a complete intervention, and if different aspects are delivered separately, such a reductionist approach may result in loss of efficacy or effectiveness. As such, yoga practices also should be delivered skillfully by experienced practitioners who can adapt the interventions for various age groups and abilities, as well as address any emerging psychological or emotional presentations.

This is part 2 of a 3-part series. Subsequent blogs will deconstruct anxiety and depression as well as outline how yoga has been proven by research to help with these conditions. Inge Sengelmann is a licensed clinical social worker and certified ParaYoga teacher who specializes in disorders of extreme stress and is committed to anti-oppression practices and decolonizing mental health.

Inge Sengelmann, LCSW, SEP, RYT is a licensed psychotherapist and certified ParaYoga teacher who promotes a practice of embodied psychology and spirituality. Visit her website at www.embodyyourlife.org.

Photo by Fernando @cferdo on Unsplash

Photo by Lina Trochez on Unsplash.