Yoga’s first principle is embodiment, and research shows that the practice of yoga tones the vagus nerve, which is implicated in numerous bodily functions and mediates the relaxation response. Through practice, we become intimately familiar with the functioning of our body, breath, and mind.

Never has our practice of yoga become so imperative. As we enter the second year of a global pandemic and the number of deaths from COVID-19 reaches almost half a million people in the US alone, some of us may be feeling the weight of stress and isolation as a new wave of dread, anxiety, grief, depression, or a gnawing sense of impending doom. Yoga may seem like a luxury not worth indulging in, or we may lack the energy to contemplate a yoga practice. Meditation, as helpful as science says it is, may be elusive to our confused and distracted minds.

We want certainty. We want to imagine an end to this endless state of unpredictability. But consider the news lately: the COVID-19 pandemic, systemic racism, and socio-political unrest, the threat domestic terrorism and police brutality, an ever-worsening climate crisis, and the undermining of democracy and equity worldwide. The battleground of our emotions, whether we want it or not, is the body. Words may fail us. As our distress remains unprocessed, undigested, and unexpressed, it manifests as insomnia, aches and pains, variable energy and vitality, and lowered immunity. We become irritable and depressed, further isolating from already diminished connections.

Yoga’s first principle is embodiment, and research shows that the practice of yoga tones the vagus nerve, which is implicated in numerous bodily functions and mediates the relaxation response. Through practice, we become intimately familiar with the functioning of our body, breath, and mind. This wisdom enables us to self-regulate our autonomic nervous system, calm our mind, and build flexibility in our thinking, feeling, and behaviors. Yoga is not about touching your toes, you see. It’s about touching your soul through time-tested practices. Grounded in the eternal and unchanging part of us, we become less fearful, more joyful, and increasingly capable of achieving our highest goals.

But where do we begin? First, understand that the “royal” path of yoga requires discipline, self-study, and surrender to a process of transformation with patience and faith. Through the practice of the various “limbs” of yoga, we become established in our essential nature – a state reflected in a mind that is calm, luminous, and undisturbed by the changing conditions of the external world. Who doesn’t want to feel peaceful and calm? The trick is to want that state badly enough that we are willing to engage in the practices that will help us reach that state.

The yoga tradition is more about the mind than it is about the body. Its inherent goal is optimal mental health through the purification of mental afflictions that block our perception of our true nature. But we need the body because it is the vehicle of consciousness. It is through the body, its brain, and nervous system that we perceive and interpret the world. Hence, we practice yamas (restraints), niyamas (observances or attitudes), asana (physical posture), pranayama (mastery of our breath/energy), pratyahara (withdrawing the senses inward), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation) in order to reach the various levels of samadhi (spiritual absorption). These are outlined in chapter 2 of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras as the steps to purify body and mind so we can experience oneness with the Absolute Reality.

We begin where we are. Simplicity is key to mastery. We make a start by understanding that a yogic lifestyle requires a commitment to non-violence, truthfulness, non-possessiveness, non-stealing, and effort to constrain our less constructive urges. These are the yamas. Non-violence and truthfulness mean that you practice within your limits and don’t demand too much of yourself, causing you to become overwhelmed and give up before you begin. Trust that every small change you make leads to big transformation. As my teacher, Yogarupa Rod Stryker likes to say, “change is the hardest yoga.” So we muster up the courage to investigate what the practice of yoga might mean to us personally.

The niyamas invite us into a life of cleanliness and purity of body and mind, contentment and gratitude as a mental attitude, disciplined effort, self-study through inquiry, and trustful surrender to Ishvara, the inner light or guiding principle of Pure Consciousness within us.

Your yoga practice may include certain purification routines in the morning, such as scraping your tongue of impurities, washing your body, wearing clean clothes, and eating more fresh than processed foods. Self-study may mean a daily inventory of helpful and unhelpful thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; a gratitude list to cultivate an attitude of contentment; and pausing to drop beyond our stressful thoughts into a higher mind for intuitive guidance.

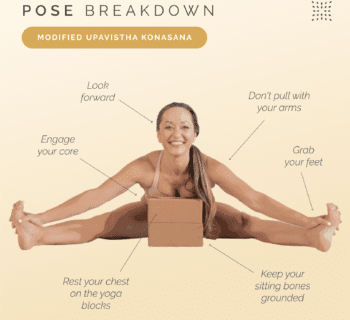

Patanjali makes it clear that asana is not the acrobatics of standing on your hands or twisting yourself into a pretzel. In fact, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika clearly states that there are 15 major poses of which several are seated meditation poses and one is savasana, the restful corpse pose. The way to master the pose, according to Patanjali, is to attain an easeful steadiness (sthiram, sukham) or stability and comfort. To “perfect” the pose requires the loosening of tension caused by too much effort, and then allowing the mind to become absorbed in contemplation of the “infinite.” For the purpose of the remaining limbs that lead to meditation, find a pose that allows you to sit comfortably for several minutes.

Pratyahara means that you commit to leave the distractions of the world – and the mind’s attachment to compulsive thinking – for long enough that you can focus on your breath with one-pointedness. If mind becomes distracted or pulled away from the focus of inner attention, keep turning the mind inward.

Here is a pranayama breath awareness practice to release tension and constriction in the autonomic nervous system: diaphragmatic abdominal breathing. You can do this lying down or seated, as long as your posture is erect, and your chest and ribs are not collapsing into the abdomen. Begin to breathe evenly in and out with most of the movement in the abdomen. The chest is relatively still as the abdomen expands on inhale and softens on exhale. Gradually invite the breath to become smooth, continuous, and uninterrupted. As your nervous system receives the message to relax, your diaphragm (a very large, dome-shaped muscle below the ribcage) will soften and release any tension or constriction. Be aware that you may feel your body twitch, and emotions that have been constricted there may arise. Allow any heat, shaking/trembling, sweating or tears to happen. These are just the processes the body uses to release stress hormones. Awareness remains steady and undisturbed. Continue to witness the release of tension in body and mind until you experience a completion marked by a renewed sense of clarity and calm vitality.

You can continue the same practice with prana dharana, a concentration of the lifeforce riding on the breath, feeling the abdomen filled with this golden stream of life energy. As the mind becomes increasingly absorbed in this light, you move into dhyana, or meditation on this object: energy in the abdomen. If you slip into a state of oneness, where you dissolve into this golden light, you’ve gotten a glimpse into samadhi, which is merging with the object of your meditation.

If you wish to extend your practice and do some self-study, you could consider journaling about your experience. What was distracting you? What helped you ease into a deeper state of relaxation? How has your physical, mental, and emotional state changed as a result of your practice? Is there something I need to do about the thoughts that were distracting me? If they were negative thoughts, can I contemplate some opposite ideas? Cultivate an attitude of curiosity, non-judgment and compassionate witness as your higher awareness investigates the processes of your conditioned mind and personality, remembering that your essential, deepest and truest self is pure, unconditioned Consciousness.

Other helpful activities to contemplate as part of your mental health practice of yoga:

Slow down and feel your body – your body is the container of your experience and the radar signaling you are stressed. Simple awareness of the body’s sensations of constriction may allow them to let go. Become aware of the polarities of constriction and expansion, fear and bliss, beauty and horror – and move awareness between the two until something changes.

Ask for help – our conditioned minds can be a minefield, especially during these trying times that have heightened our awareness of personal, collective, and ancestral traumas. Don’t struggle alone. Reach out to a trusted teacher or therapist and share your struggles – with practice or with life. Feeling our feelings in the safety of a caring witness is an important way to “digest” the stress hormones released in the body and the mental impressions in the mind.

Create a sangha – We are social beings designed to be in community. Find or create a trusted community of like-minded souls with whom you can share experiences as well as helpful resources. Notice how your body and breath respond when you are feeling safe in community. Any groups with shared interests are helpful, whether they are social, professional or spiritual. Remember the strength and resilience of your community.

Lift your spirits – by reading inspirational literature and/or the scriptures of your spiritual tradition. Listen to helpful podcasts by luminaries in various traditions. Watch documentaries or comedies – whatever your wise mind tells you will be helpful in the moment. Expand your consciousness by listening to experiences beyond your own. Seek to understand those different than you. Remember that you are not alone. All of humanity is in the same boat and there are many helpers to guide us.

Play! – it’s important to find opportunities for rest and recreation to help reset your nervous system as well as find joy in the midst of turmoil. By making time for healthy pleasure, especially with others, we tap into the joy that is ever present in our hearts. This is a good way to balance (not avoid) the states of grief or depression that are stimulated by current conditions.

Fantasize! – our bodies respond to the thoughts and images we hold in our minds. It’s like being in a movie theater, but the screen is in our mind. So let your imagination run wild and experience the shifts in your nervous system as you visualize yourself on a remote beach, diving deep in the ocean, or skiing down a mountain. Again, this is not about avoidance, but rather it is providing respite to an over-burdened nervous system.

Grounding and Orienting – the more present we can be in the current moment, the easier it will be to reset our nervous system to a helpful balance. Most of our distress is caused by stressful thoughts about the past or the future, both of which are not real in the present moment. Orienting to safety and grounding in our bodies through the 5 senses, feeling the stability and strength of bones and muscles, can help us become calmer.

Focus on what you can control – there may not be a lot you can control in your community and the world, but you can establish certain predictable patterns in your life, such as regular and healthy meals, meditation moments, nighttime rituals to prepare for an early night’s sleep, scheduling exercise as well as social connection time, even if it’s electronically.

Inge Sengelmann, LCSW, SEP, RYT is a licensed psychotherapist and certified ParaYoga teacher who promotes a practice of embodied psychology and spirituality. Visit her website at www.embodyyourlife.org.

Photo by Sage Friedman on Unsplash