Padmāsana, or Lotus Pose, is one of yoga’s most iconic and revered seated postures. For most practitioners, their first attempt at Lotus quickly reveals that this serene-looking posture is far more challenging than it appears.

The word Padmāsana (Sanskrit: पद्मासन) is formed from two roots: padma (पद्म) meaning lotus, and āsana (आसन) meaning seat or posture. Together, Padmāsana is the Lotus Seat — a position symbolizing purity, awakening, and spiritual unfolding.

Padmāsana, or Lotus Pose, is one of yoga’s most iconic and revered seated postures. For most practitioners, their first attempt at Lotus quickly reveals that this serene-looking posture is far more challenging than it appears.

The word Padmāsana (Sanskrit: पद्मासन) is formed from two roots: padma (पद्म) meaning lotus, and āsana (आसन) meaning seat or posture. Together, Padmāsana is the Lotus Seat — a position symbolizing purity, awakening, and spiritual unfolding.

The Symbolism of the Lotus

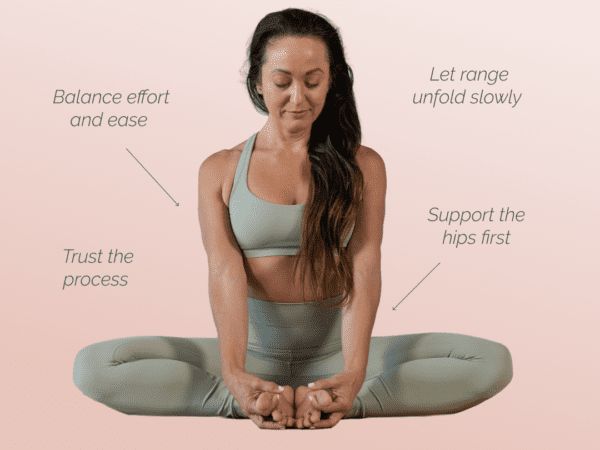

Preparing the Body for Padmāsana

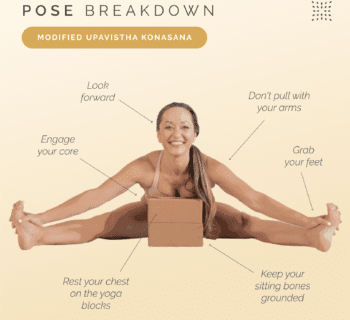

How to Enter Padmāsana: Step by Step

-

Sit on the floor with your legs extended in front of you (Daṇḍāsana, Staff Pose).

-

Bend your right knee and draw it in close to your body. Ensure the knee joint is fully closed.

-

Externally rotate the right hip joint and drop the knee outward. Keep the knee joint snug, so your calf rests against your thigh.

-

Slip your right hand under your knee and your left hand under your right foot. Lift the right foot and gently place it into your left hip crease. The sole should face upward — padma resting near your lower abdomen, close to the navel.

-

Keep the foot flexed (demi-point) to protect the ankle. Align your shin so there’s no excessive twisting or ‘sickling’ of the foot.

-

Pause here in Ardha Padmāsana (Half Lotus Pose). Breathe and listen to your body. If there’s sharp pain in the knee or ankle, slowly exit the pose — never force it. When you feel stable and open enough, bring the left foot up:

-

From Half Lotus, slide your left foot over the right leg and into the opposite hip crease. Keep the knee joint closed as you guide the foot across.

-

Both feet should rest symmetrically, soles turned upward, with heels snug to the lower abdomen on either side of the navel.

Safety First: Padmāsana Contraindications

Lotus Pose places significant demand on the hips, knees, and ankles. If you have injuries in these joints, practice under the guidance of an experienced teacher, physical therapist, or doctor. Sharp pain is a sign to stop immediately — never push through joint pain in pursuit of the shape.

Integrating the Posture

Once in Padmāsana, engage the whole body:

-

Draw the lower belly in, gently lift the pelvic floor (mūla bandha, मूल बन्ध).

-

Elevate the sternum, lengthen the spine upward, and softly drop the chin.

-

Avoid rounding the lower back — instead, rise tall from the base of the spine.

The Lotus Journey

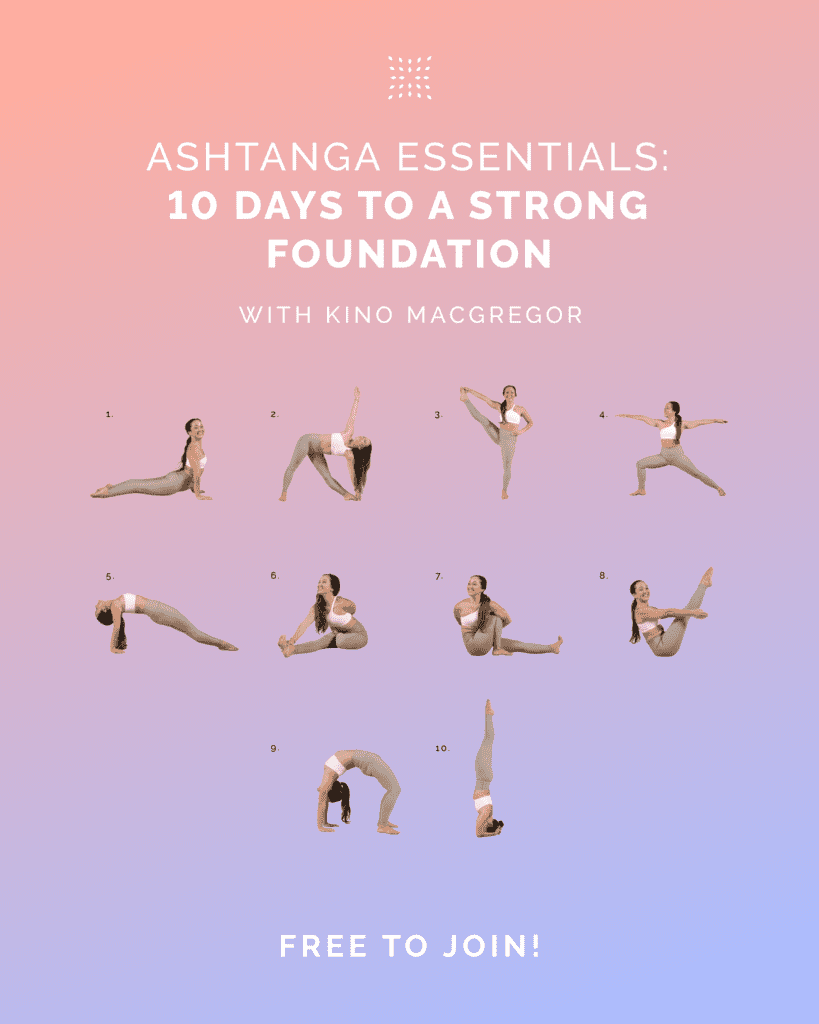

In Ashtanga Yoga, Padmāsana is woven into many postures: Garbha Piṇḍāsana, Karandavāsana, Ūrdhva Kukkuṭāsana, to name a few. If full Lotus remains elusive, remember: its true gift lies in the journey, not just the final shape. The patient cultivation of open hips, mindful breath, and inner focus is where the lotus truly blooms.

Some students find Padmāsana accessible early on. For others, it may take years — or a lifetime — to approach fully. Life changes, age, or injuries may close the petals again. And yet, the spiritual seeds planted through the practice continue to grow deep roots of peace, compassion, and resilience.

As my teacher often reminds me: the real benefits of yoga are never just physical. They blossom over time as more calm, kindness, and love — just like the lotus rising pure from the mud.

Explore more Lotus resources and guided practices here: