By Kino MacGregor

The Sacred Geometry of Triangle Pose: History, Benefits, and Symbolism of Utthita and Parivr̥tta Trikoṇāsana

Among the archetypal forms of modern yoga, few are as enduring or as evocative as the Triangle Pose and its Revolved counterpart. These asanas are not only shapes of physical discipline but also living symbols of stability, transformation, and sacred geometry. To step into Utthita Trikoṇāsana (Extended Triangle Pose) or Parivr̥tta Trikoṇāsana (Revolved Triangle Pose) is to embody a lineage of strength and subtlety, a practice that unites the body’s architecture with the soul’s search for balance.

The Meaning Written in the Name

The very names of these postures are teachings in themselves. Trikoṇa is formed from tri (three) and koṇa (angle), meaning triangle, the simplest and most stable of all geometries. Āsana means seat or posture, the foundation of embodied practice. Utthita means extended, outstretched, a word that hints at the expansive reach of the limbs in classic Triangle. Parivr̥tta comes from pari (around, surrounding) and vṛt (to turn, revolve), signifying not just rotation of the torso but the alchemy of transformation. The postures themselves are reminders that yoga is a language written into the body, where even the names carry the echo of the sacred.

A Modern Pose with Ancient Resonance

Though they feel timeless, neither Triangle nor Revolved Triangle appear in the medieval Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā or Gheraṇḍa Saṃhitā. These texts focus on seated forms and a handful of other postures. Standing poses such as Triangle emerge much later, shaped in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the Mysore palace tradition under Sri T. Krishnamacharya. The illustrated Śrītattvanidhi foreshadows this development, showing over a hundred postures, though under different names and contexts. It was through Krishnamacharya’s teaching—and later, the works of B.K.S. Iyengar and K. Pattabhi Jois—that Triangle became codified and spread around the world.

Unlike the seated meditative shapes of haṭha’s early manuals, Triangle and its revolved partner combine inner meditative focus with strength and mobility. They became a language through which yoga could address not only the subtle body but also the pressing needs of vitality and discipline in daily life.

One Pose, Many Traditions

Different traditions interpret the Triangle in their own ways. In Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga, Utthita Trikoṇāsana A is the extended form, while B refers to the revolved variation, both practiced with a precise vinyasa count, dr̥ṣṭi (gazing point), and five steady breaths. Iyengar Yoga distinguishes between Utthita Trikoṇāsana and Parivr̥tta Trikoṇāsana, teaching them with props, walls, and ropes to refine alignment and therapeutic application. In Sivananda Yoga, “Trikonasana” refers instead to a side bend, taught as one of twelve core postures. Contemporary vinyasa blends freely among these traditions, some teaching with shorter stances and neutral pelvis for safety, others maintaining the long stance and deep rooting of the classical form.

The Body’s Fire: Benefits and Energetics

Physically, Utthita Trikoṇāsana B strengthens the legs, stretches the hamstrings and adductors, and decompresses the spine through lateral extension and rotational elongation. It expands the ribs, releases the diaphragm and encourages deeper breathing. Parivr̥tta Trikoṇāsana recruits the power of the twist, mobilizing the thoracic spine, strengthening the obliques, and compressing the abdominal cavity in a way that massages the liver, pancreas, and intestines. Trikoṇāsana stimulates circulation, lymphatic flow, and respiration, enhancing the body’s ability to detoxify and renew.

Energetically, the two asanas awaken maṇipūra cakra, the solar plexus center of vitality and will. The expansive opening of Triangle brushes against anāhata cakra, the heart center, encouraging receptivity and openness. The revolving motion of Parivr̥tta Trikoṇāsana is traditionally described as wringing out stagnant prāṇa, like squeezing water from a cloth, leaving the channels clear and the perception sharpened. What we feel as stretch and twist is also the tending of agni, the inner fire that transforms both food and experience into energy.

The Fire’s Shadow: Contraindications and Care

This alchemy of steadiness and transformation must be practiced wisely. Students with sacroiliac instability, slipped discs, or acute lower back pain should be cautious, as twists can misdirect force into vulnerable areas. Pregnant practitioners are advised to avoid deep revolved variations that compress the abdomen. Those with low blood pressure may feel dizzy, and those with neck sensitivity should keep the gaze neutral instead of upward. Even in mythic terms, the fire of Triangle must be tended carefully—too much force and it burns, too little foundation and it flickers.

Adapting the Triangle

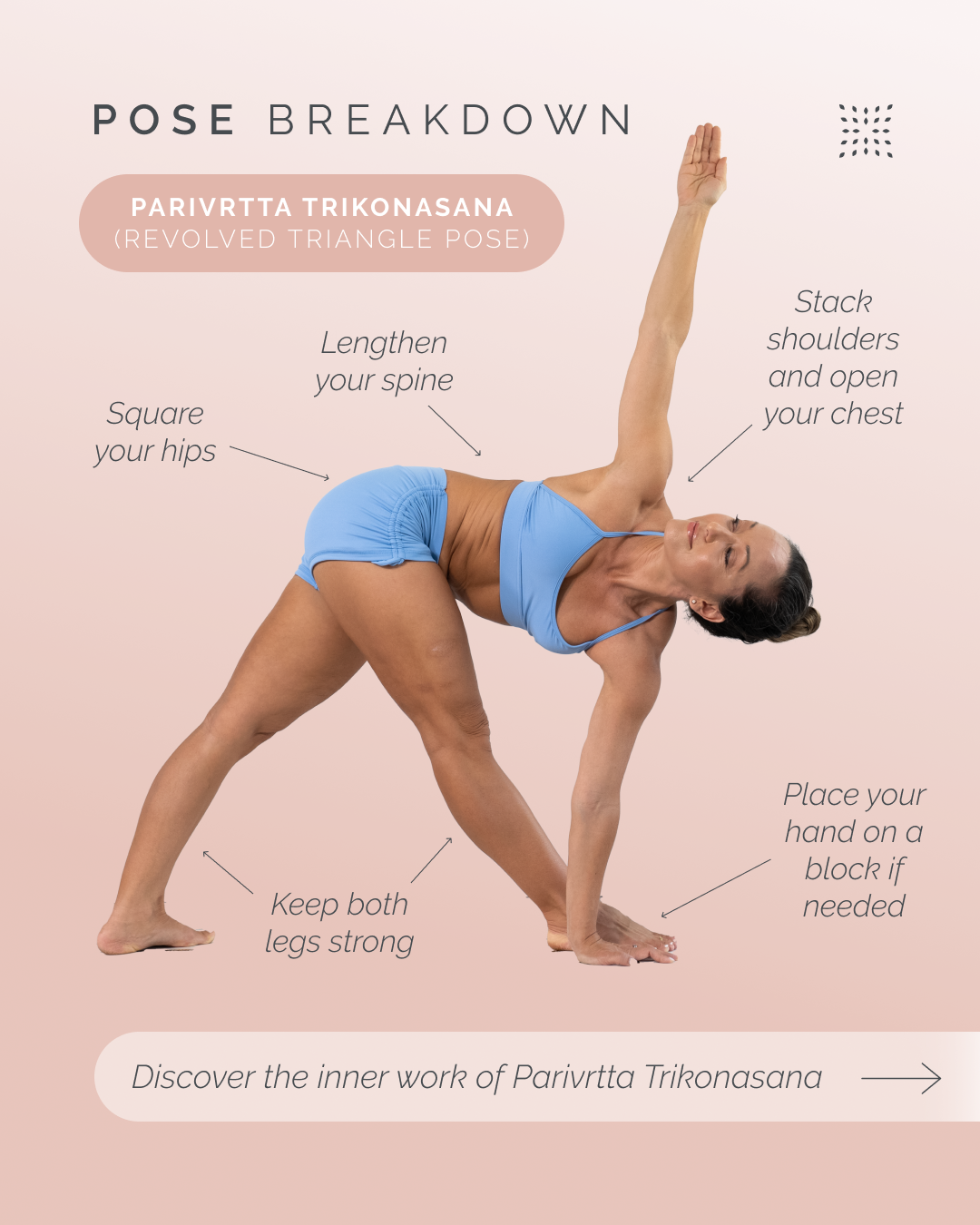

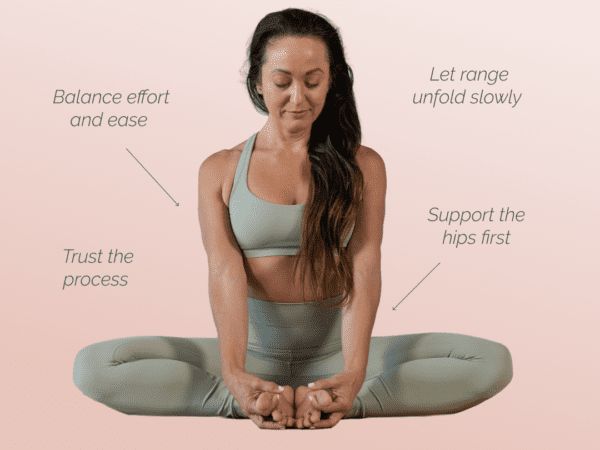

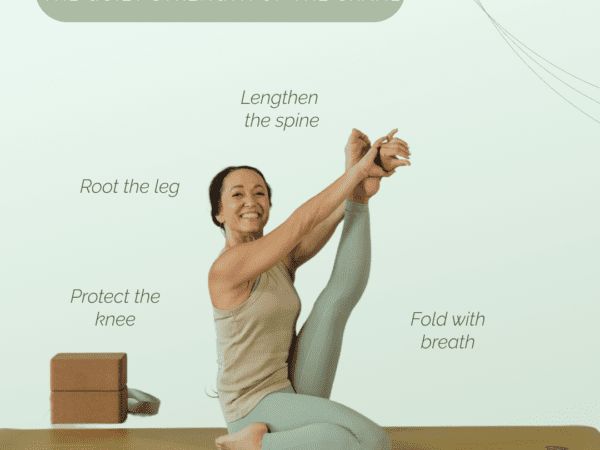

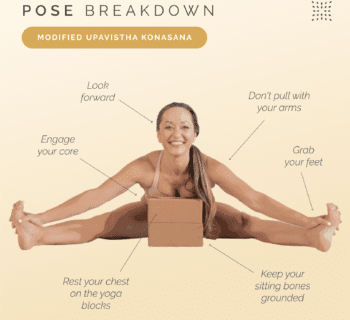

The essence of Triangle does not lie in depth of fold but in steadiness of foundation. A block or chair beneath the lower hand allows the posture to unfold safely without sacrificing alignment. Practicing against a wall provides feedback for the spine and protects against over-rotation. In the revolved variation, finding an appropriate positioning of the back heel helps redirect the twist into the thoracic spine instead of straining the sacrum. For those with mobility challenges, seated versions in chair yoga open the chest and extend the spine, carrying the same symbolic resonance of rooting, lengthening, and revolving. To adapt the triangle is not to diminish its power but to recognize that sacred geometry is available to every body in every season of life.

Myth and Symbol: The Cosmic Triangle

Beyond alignment and anatomy, Triangle carries a mythic charge. The upward-pointing triangle symbolizes fire and aspiration, often associated with Śiva; the downward triangle symbolizes water and receptivity, linked with Śakti. Together, their union in the Śrī Yantra represents the cosmic balance of opposites. In Vedic ritual, the triangular altar (vedi) was the site of the sacred fire where offerings were transformed into merit. In the body, the triangle echoes the stable base of the pelvis and the triune structure of lower energy centers.

To stand in Utthita Trikoṇāsana is to embody this sacred fire altar, steady and clear. To revolve the triangle is to set that altar into motion, fanning the flame into a wheel of transformation. What was stable becomes dynamic, what was external turns inward, and what was familiar reveals its hidden side. The Revolved Triangle asks us to look behind, to twist perception, to find courage in reversal and to see with new eyes.

Alignment in Practice

Begin in samasthitiḥ, steady at the front of the mat. Step the feet apart, a little less than the length of one leg, and extend the arms wide. Engage the pelvic floor and lower belly, lengthen the spine, and root through the bases of the big toes, drawing energy up through the thighs into the pelvis. For the revolved variation, turn the back foot slightly out (between 45 and 90 degrees) and align the pelvis forward. Options vary: heel-to-heel alignment for stability, heel-to-arch for deeper stretch, or a small gap for balance.

As you exhale, fold forward, aligning sternum, navel, and pubic bone toward the front knee. Place the opposite hand outside the foot or onto a block, keeping the legs steady and the spine long. With each inhale, lengthen; with each exhale, revolve. Avoid collapsing or torquing the pelvis; let the twist arise from the thoracic spine. Lift the top arm, stack the shoulders, and allow the gaze to rise if the neck is comfortable.

The Living Flame of the Triangle

Taken together, Utthita and Parivr̥tta Trikoṇāsana form a sacred pair. One is the still temple of fire, rooted and clear. The other is the turning flame, restless and revelatory. Practiced with awareness, they strengthen and cleanse the body, awaken the chakras, and embody the eternal principle of yoga: steadiness amidst movement, clarity amidst change. In their geometry we find not only alignment of limbs but alignment of spirit—the reminder that yoga is a revolving of perception, a geometry of the sacred made visible through the body.