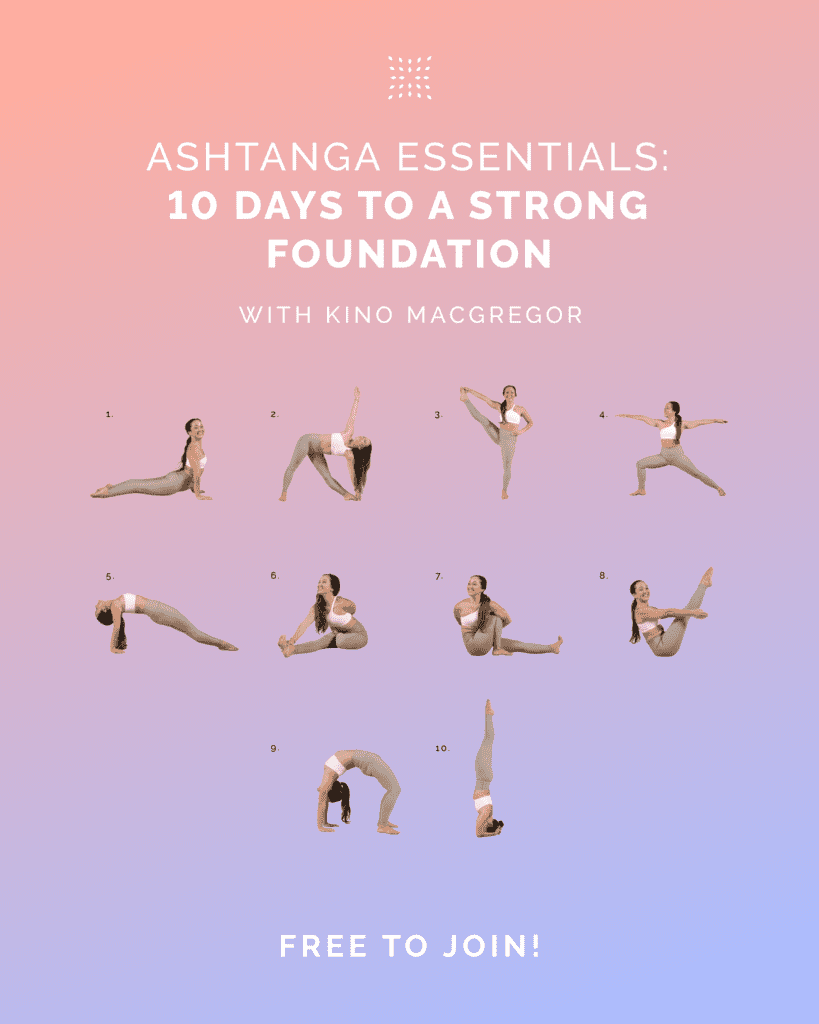

By, Kino MacGregor

Putting your leg behind your head is not really the point. Yes, Eka Pāda Śīrṣāsana demands extraordinary physical access: deep hip rotation, supple hamstrings, and a spine capable of both strength and surrender. But in the deeper language of yoga, the question is never just “Can you do the pose?” The real inquiry is always, “What is the pose teaching you about yourself?”

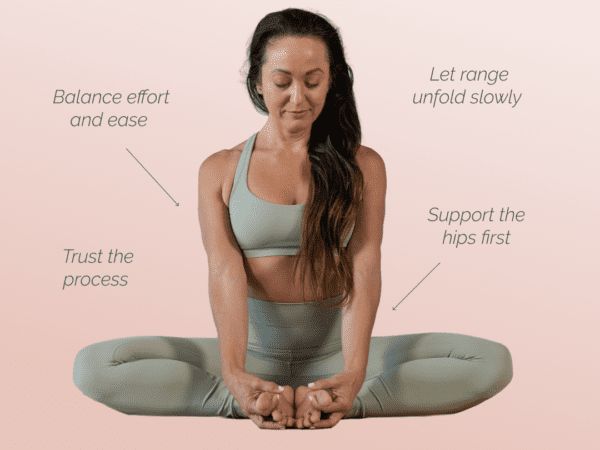

In the Yoga Sūtra, Patañjali defines āsana not as an external achievement but as an internal state: sthira sukham āsanam (YS 2.46), a posture that is steady and easeful. This deceptively simple definition carries profound implications. Even the most intricate shapes must be infused with tranquility and firmness. Without that inner balance, no matter how advanced the outer form may appear, the essence of yoga is lost.

Eka Pāda Śīrṣāsana, literally “One Leg Behind the Head Pose,” is not found in early textual sources such as the Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā or Gheraṇḍa Saṃhitā. It emerges instead from the twentieth-century lineage of postural yoga, particularly within the Ashtanga tradition as taught by K. Pattabhi Jois, and later codified in works like B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Yoga. Though modern in origin, the posture draws on timeless principles. It becomes a living expression of tapas (austerity), svādhyāya (self-inquiry), and īśvarapraṇidhāna (surrender to the divine), the three limbs of kriyā yoga (YS 2.1).

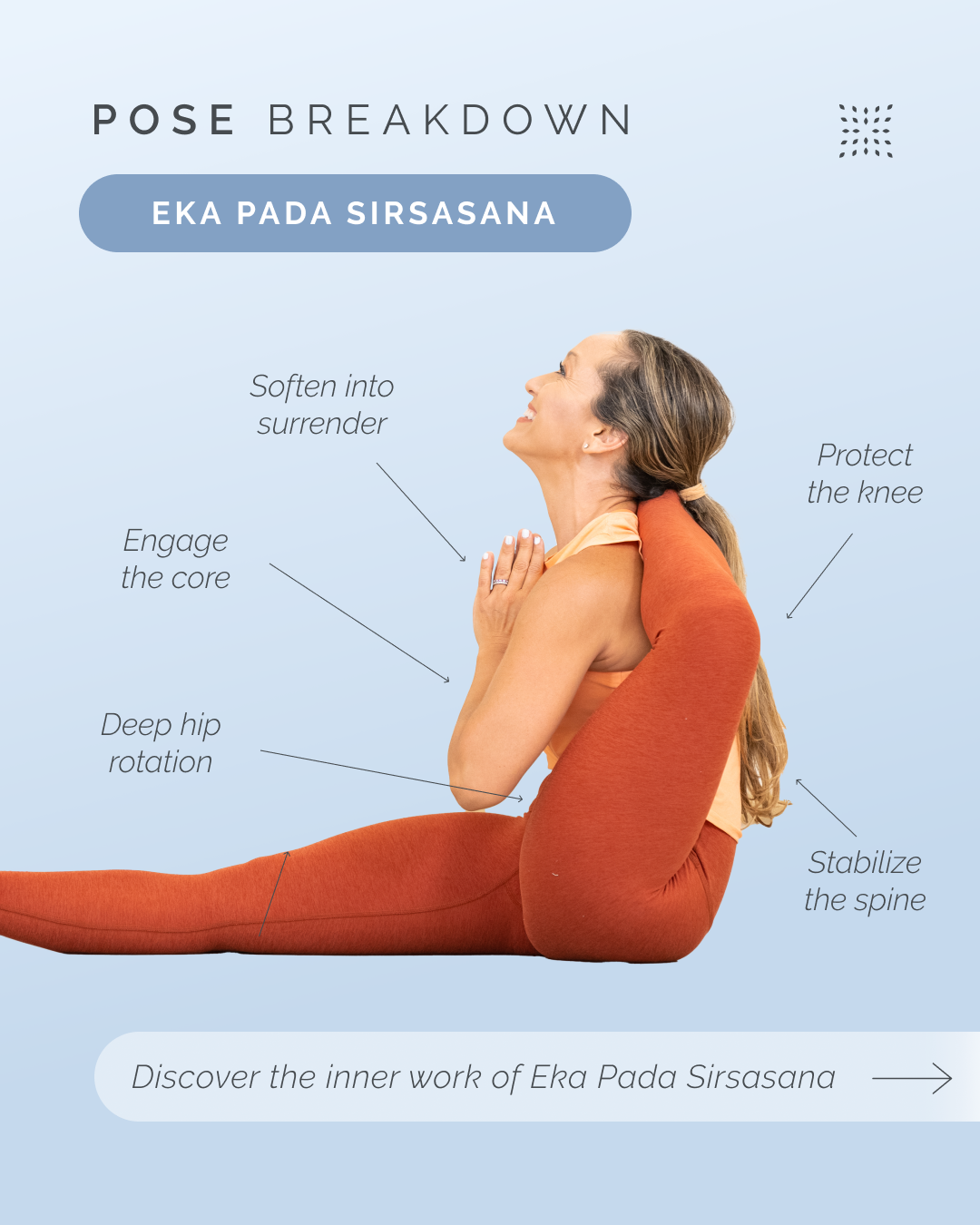

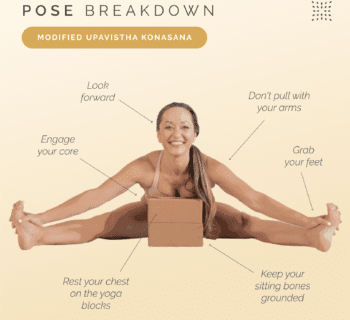

Technique and Alignment

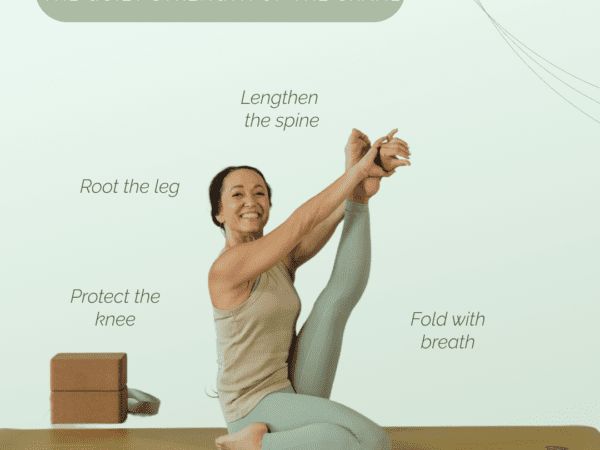

Anatomically, the posture demands precision and patience. From a Western perspective, safe entry requires deep external rotation of the hip joint, ideally facilitated by a widening of the lower back and sacrum, along with a slight posterior pelvic tilt. It is important to avoid collapsing into the lumbar spine or leaning too far backward. The knee must be carefully protected against strain, while the spine remains stabilized through core support and breath awareness. The leg is not forced behind the head, as it might appear from the outside. Instead, a combination of hip flexion, external rotation, mobility, flexibility, and stability gradually leads the hip through this range of movement. The body is guided there over months or years, supported by mindful preparation and neuromuscular intelligence.

Many practitioners rush toward the final shape without honoring the structure that supports it. This can place pressure on the sacroiliac joint, cervical spine, or sciatic nerve. The deep stretch of the piriformis may feel therapeutic for some, but it can trigger symptoms of nerve compression in others. For this reason, Eka Pāda Śīrṣāsana carries real contraindications, especially for those with knee injuries, disc herniation, SI joint dysfunction, or sciatica. Flexibility alone is not enough. The posture requires integration: strength to support openness, and awareness to sustain it.

And yet, for all its physical demands, Eka Pāda Śīrṣāsana is rarely about physicality alone. More often, it becomes a mirror. It reveals our inner terrain: our resistance, our self-doubt, our desire to push through pain just to say, “I can.” Some students may never bring the leg fully behind the head. That does not matter. What matters is how we meet the process. What rises up in the attempt? Can we stay present with it? Can we soften instead of strive?

Eka Pāda Śīrṣāsana in the Ashtanga Yoga Second Series and Iyengar Yoga

Within the Ashtanga method, Eka Pāda Śīrṣāsana appears in the Intermediate Series, known as Nādī Śodhana, the sequence designed to cleanse and balance the subtle channels of prāṇa. This placement is significant. By the time a student reaches this posture, the body has already been tempered by the Primary Series, with its focus on forward folds, hip opening, and foundational strength. The Intermediate Series shifts the emphasis toward backbending, deeper hip rotation, and a more refined awareness of energy flow.

I still remember my first encounters with Eka Pāda Śīrṣāsana in Mysore. At the time, the posture felt more like an impossible dream than a real possibility for my body. Day after day I placed my leg on my shoulder, inching it higher, only to meet resistance in my hips and doubt in my heart. I also watched my teachers help countless students work through this āsana. For some, it came within months; for others, it took years. In both cases, the lesson was the same: yoga is not about conquering the body but about staying present in the process. The real practice is patience, humility, and surrender.

Eka Pāda Śīrṣāsana is one of the most demanding postures in this sequence, both physically and mentally. For many practitioners, the sheer challenge of the shape brings up resistance, frustration, or self-criticism. In this way, the posture acts as a crucible. It burns away impatience and reveals the habits of the mind. To work with it requires humility, patience, and faith in the slow unfolding of practice.

Within the vinyasa framework of Ashtanga, the posture is not an isolated event but part of a rhythm of breath and movement. Each inhale and exhale prepares the body for entry, sustains it during the hold, and carries it safely into the next transition. The repetition of this cycle day after day gradually erodes the restless grasping of the mind, leaving space for steadiness, presence, and surrender.

Iyengar Yoga approaches the posture through structural alignment and careful preparation. Props such as straps, bolsters, and walls are not crutches but tools of intelligence. A practitioner may spend months in Agnistambhāsana or Supta Pādaṅguṣṭhāsana before attempting leg-behind-the-head. The focus is not on attaining the final shape but on cultivating the actions that make it safe and sustainable. This slower, methodical approach reflects a different, but equally authentic, interpretation of yogic values: precision, humility, and the pursuit of inner steadiness.

Deeper Lessons and Guidance

For practitioners with extreme flexibility, the pose may come easily. Yet for those with hypermobility, the recommendation is to balance openness with strengthening and stabilization. For them, the lesson lies not in expanding range but in cultivating strength and groundedness. The Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā affirms that the fruit of āsana is not acrobatic prowess, but aṅga lāghavam—lightness of limbs, clarity of energy, and freedom from disease (HYP 1.17). Strength is not the opposite of flexibility but its companion. Together, they create the balanced vessel required for inner awakening.

Ultimately, Eka Pāda Śīrṣāsana is not about domination of the body. It is a devotional gesture, a form of surrender. The leg rests not on the head but behind it, symbolically humbling the ego and offering the body to something higher. Whether or not the posture is ever fully realized matters less than how we walk the path toward it. The transformation unfolds along the way.

To practice yoga is to walk the razor’s edge between effort and ease, discipline and surrender. This posture, like so many others, asks: How willing are you to stay present with what is difficult? Can you find softness within intensity? Can you breathe here?

If you listen closely, Eka Pāda Śīrṣāsana may whisper the same truth that all sincere practice eventually reveals: yoga is not about the shape you make. It is about the shape the practice makes of you.