At first glance, Vṛkṣāsana -the Tree Pose – looks deceptively simple. A single leg roots into the ground, the other folds into the standing thigh, the arms rise, join together or open like branches. But beneath its stillness lies a web of history, mythology, and deep physical intelligence. In this one shape, the ancient and the modern, the symbolic and the practical, meet.

Roots in Language and Tradition

The Sanskrit name comes from vṛkṣa, meaning “tree,” and āsana, meaning “seat” or “posture.” Like many traditional postures, Vṛkṣāsana is more than a description of form, it is an image that guides the mind. To take this seat is to embody the steadiness of a tree: grounded yet reaching, anchored in the earth yet touching the sky.

The earliest known written instructions for Tree Pose appear in the Gheraṇḍa Saṃhitā (c. 17th–18th century), which describes:

“Placing the foot at the root of the opposite thigh, stand like a tree. This is known as Vṛkṣāsana.”

(vāma-ūru-mūla-deśe ca yāmyaṃ pādaṃ nidhāya tu / tiṣṭhati vṛkṣavad bhūmau vṛkṣāsanam idaṃ viduḥ, 2.36)

But the idea of the one-legged yogin predates these haṭha yoga manuals. Temple sculptures, like the monumental Pallava carvings at Mahābalipuram, depict sages balancing on one leg for extended periods, engaged in tapas (austerities) to concentrate the mind and purify the spirit.

The Legend of King Bhagiratha: A River Brought by Stillness

Long before Tree Pose was a feature of yoga classes, it was the stance of a king whose devotion altered the very landscape of the earth. King Bhagiratha was heir to a kingdom weighed down by an ancient curse: his ancestors’ ashes lay in limbo, denied final liberation. Only the purifying waters of the celestial river Gaṅgā could cleanse the 60,000 sons of King Sagara who were cursed by the sage Kapila and grant peace to their souls.

But Gaṅgā flowed only in the heavens, in realms beyond mortal reach. To bring her down to earth required an act of such devotion, focus, and endurance that few could attempt it. Bhagiratha withdrew from his royal life and retreated into the wilderness. There, beneath the open sky, he stood on a single leg, arms lifted, gaze unwavering, a human pillar rooted in the ground like the trunk of a great tree.

Days turned into months, and months into years. Sun scorched his skin, wind rattled his frame, rain poured down in cold sheets. Yet Bhagiratha did not move. This was not stubbornness but tapas, the heat of sustained practice that burns through all distractions. The stillness of his body became a beacon to the gods, a wordless prayer offered through flesh and bone.

Finally, Gaṅgā agreed to descend. Yet her power was so immense that if she fell freely from the heavens, she would shatter the earth. Bhagiratha then prayed to Lord Śiva, who caught her mighty torrent in the coils of his matted hair and let her flow gently to the plains. The river wound its way to the place where Bhagiratha’s ancestors lay, washing over them and releasing them into peace.

In some tellings, Bhagiratha’s penance is described as a one-legged meditation lasting a thousand years, a feat so far beyond human measure that it can only be understood as a metaphor for unshakable purpose. When Tree Pose is called Bhagirathāsana, it honors this legendary act: the capacity to stand unmoved in pursuit of something sacred.

For the modern practitioner, the story is a reminder that balance is not merely about physical steadiness. It is about aligning our entire being, body, breath, and intention toward what matters most. In every breath of Vṛkṣāsana, we have the chance to taste that same quiet determination, to stand rooted in the present moment until grace, like the Gaṅgā, begins to flow.

The Sacred Trees of Indian Thought

In Indian philosophy and spirituality, the tree is no ordinary plant, it is a cosmic archetype. The aśvattha, or sacred fig (Ficus religiosa), is revered across Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions. The Ṛg Veda praises it, the Bhagavad Gītā describes it as the eternal upside-down tree whose roots are above and branches below (15.1–4), and the Kaṭha Upaniṣad mirrors this image to speak of the soul’s journey.

The aśvattha is also the Bodhi Tree beneath which the Buddha awakened. In Ayurveda, its bark, leaves, and fruit have been used for centuries to treat ailments from cough to skin conditions, blending the sacred and the medicinal.

Another symbolic tree is the kalpavṛkṣa, the wish-fulfilling tree of Purāṇic mythology. From kalpa (eternity, cosmic time) and vṛkṣa (tree), it grows in heaven and grants the desires of those who come under its shade. In art, it is depicted laden with blossoms and surrounded by attendants, a vision of abundance and shelter. When we stand as a tree in yoga, we stand in the lineage of these world-trees, steady, generous, and alive with connection between heaven and earth.

The Living Tree in the Body

In modern yoga, Vṛkṣāsana appears in most lineages, though with subtle differences. In Iyengar Yoga, emphasis falls on precision of alignment and the elongation of the spine. In Krishnamacharya’s tradition, the pose may prepare the hips for lotus variations. In Ashtanga Yoga, there is no standalone Tree Pose in the Primary Series, but Ardha Baddha Padmottānāsana contains a close cousin, a one-legged balance with half lotus, that carries the same hip rotation and steadiness of gaze.

Physically, the benefits of Vṛkṣāsana are both foundational and far-reaching. It cultivates balance of mind and body, strengthens the standing leg, and gently opens the hip of the lifted leg. It sharpens dr̥ṣṭi (the yogic gaze), improves orientation of the body’s center of gravity, and prepares the hips for deeper openings found in postures like padmāsana.

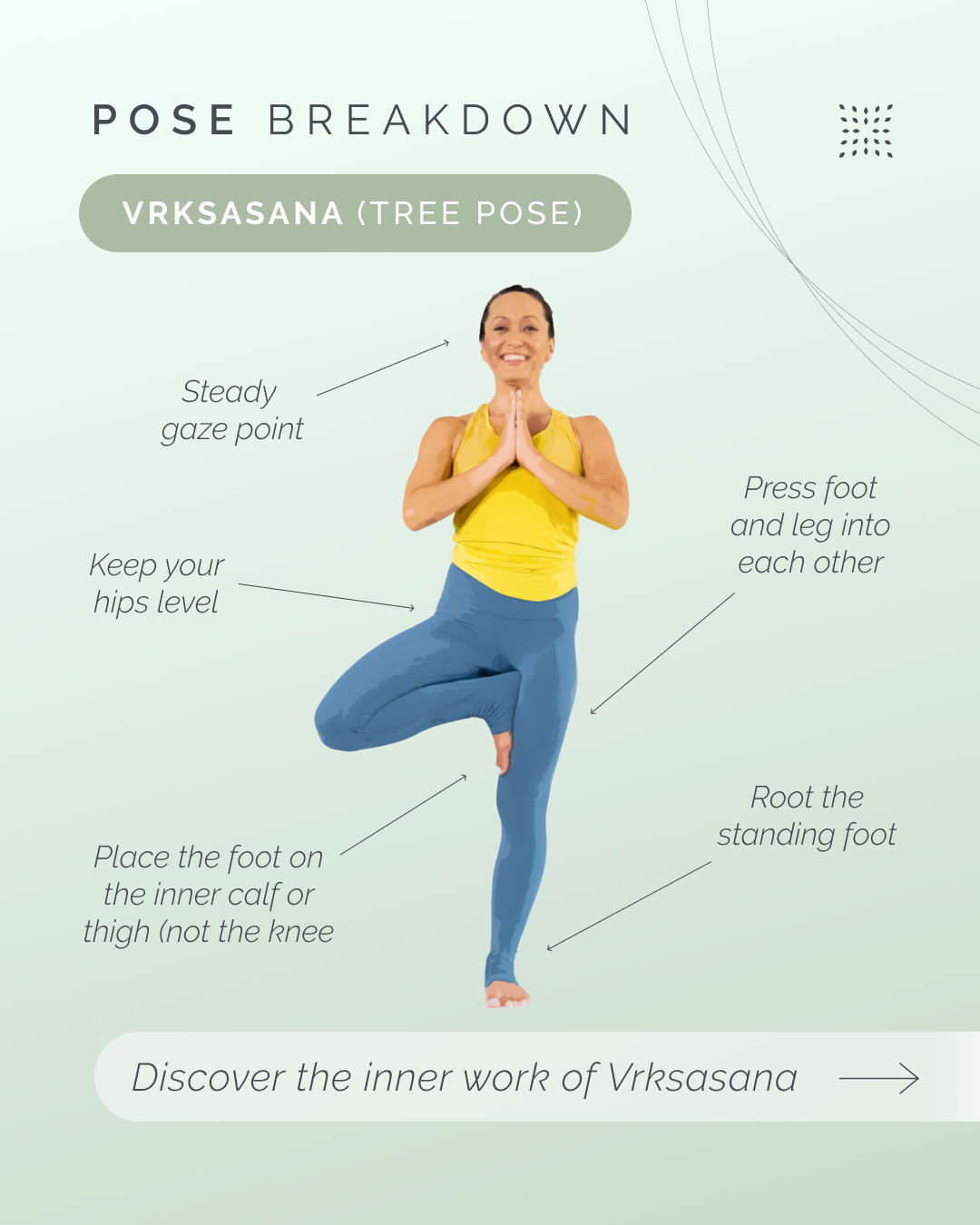

Technique and Alignment in Vṛkṣāsana

Begin in Tāḍāsana, feet together, grounding evenly through all four corners of each foot. Feel the inner arches lift and the thigh muscles gently engage. Shift your weight into your right foot without letting the hip pop out to the side. Keep the pelvis level and the standing leg straight but not locked.

Bend the left knee and bring the sole of the left foot to rest on the inside of the right thigh. Press foot and thigh into one another with equal strength. This mutual action stabilizes the pelvis and keeps the hips facing forward. If the foot does not comfortably reach the thigh, place it lower on the leg, but never directly on the knee joint.

Draw the tailbone down and lengthen up through the crown of the head. Soften the ribs in and keep the spine tall. Lift the sternum as you reach the arms overhead, either joining the palms or keeping them shoulder-width apart with the shoulders relaxed away from the ears. Keep the dr̥ṣṭi steady at eye level or slightly above.

Maintain a gentle engagement of the lower belly, allowing the breath to deepen and the whole body to feel both rooted and light. As you hold, imagine the stability of your standing leg as the trunk of a tree and your lifted arms as branches opening into space.

Safety, Accessibility, and Variations

The tree grows in many forms. For those with knee injuries, balance disorders, vertigo, or recovering from stroke, modifications are essential. You might practice a “planted tree,” keeping the ball of the lifted foot on the ground with the knee opening outward. Resting the foot below the knee, rather than above, reduces torque on the joint. Standing near a wall or holding the back of a chair offers stability without strain. Even seated, the shape can be adapted by one foot resting on the opposite thigh or shin, spine upright, gaze steady.

Tips for Stability and Strength

True balance in Vṛkṣāsana comes not from forcing the body into place, but from cultivating an inner network of support. Instead of using the hands to push the knee open, recruit the deep six hip rotator muscles to externally rotate the lifted leg. Press the sole of the foot into the standing thigh, and press the thigh back into the foot, an equal and opposite action that centers the pelvis.

Set your gaze (dr̥ṣṭi) on one unmoving point; the steadiness of your eyes will echo through your entire nervous system. Draw the lower abdomen gently in and up, engaging the bandhas, and create space between ribs and hips. Hold for at least five slow breaths, letting the posture become a dialogue between rootedness and lift.

Standing as a Tree

When you step into Vṛkṣāsana, you are stepping into a posture that has been shaped by centuries of devotion, philosophy, and practice. You join the ascetics carved in stone, the kings of legend, and the living trees of India’s sacred landscape. The body learns balance and strength; the mind learns patience and focus.

By, Kino MacGregor

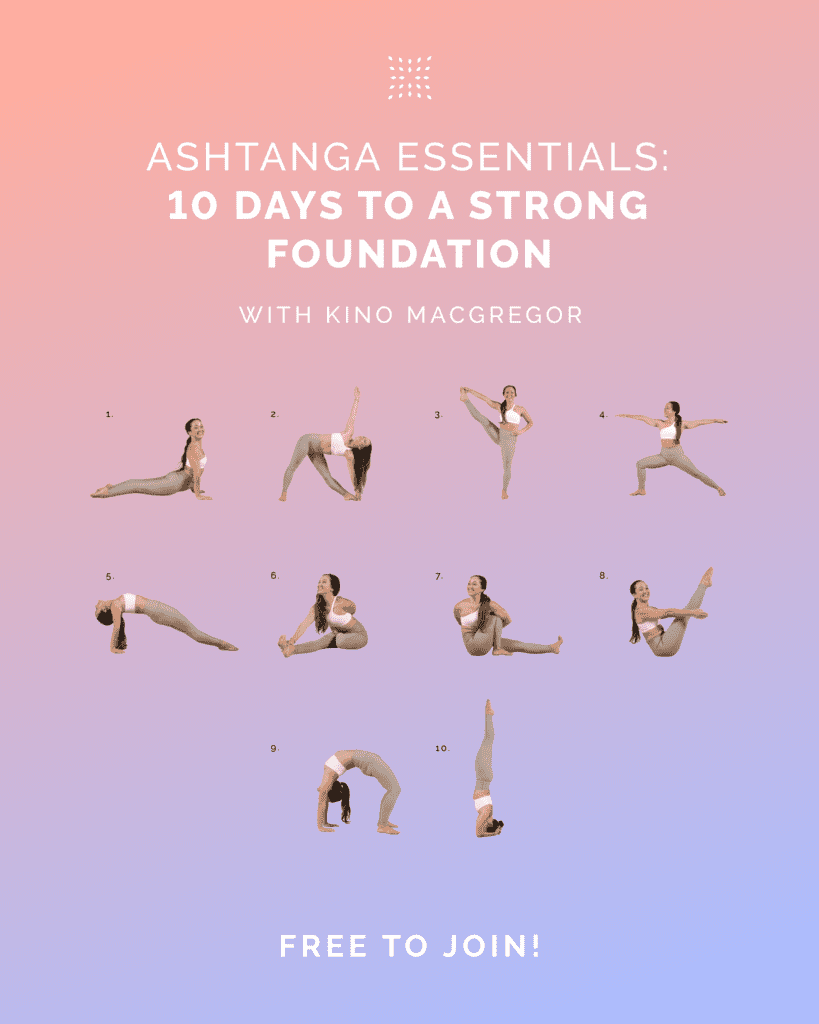

Ready to put your Tree Pose into practice? Join us for classes that will help you refine your Vṛkṣāsana, strengthen your balance, and deepen your connection to this iconic posture. Whether you’re brand new or looking to master the finer points, our expert-led classes will guide you every step of the way.