Trikoṇāsana: Entering the Triangle of Truth

By Kino MacGregor

In the sacred geometry of yoga, every posture is more than mere shape, it is a threshold. A portal. And among the first of these gateways, early in nearly every sequence, we meet the triangle: Trikoṇāsana, the three-angled pose.

The name comes from Sanskrit:

Tri means “three,”

Koṇa means “angle” or “corner,”

and Āsana means “seat” or “dwelling.”

So Trikoṇāsana is not simply the “triangle pose”, it is the posture where we take our seat within the angles of existence. It is the sacred geometry of embodiment, a shape we don’t merely form with our limbs but enter with our awareness.

Though Trikoṇāsana is not mentioned in early yoga scriptures like the Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā, the triangle itself holds profound symbolic weight across Indian philosophy. In Yantra symbolism, the triangle is the primal seat of power and transformation. The three Guṇas; Sattva (clarity), Rajas (activity), and Tamas (inertia) – and the tripartite structure of reality in Vedānta – knower, known, and knowing – all point to the mystical power of “three.” In this posture, those triads are not abstract, they are felt, lived, and harmonized.

Trikoṇāsana first appears by name in Krishnamacharya’s 1934 Yoga Makaranda, where it is taught not just as a geometric alignment but as a therapeutic tool – a posture to balance the nervous system, stimulate circulation, and relieve pain through slow, conscious breath and sustained presence. His students – including B.K.S. Iyengar and K. Pattabhi Jois – carried the posture into modern systems. In Iyengar’s Light on Yoga (1966), Trikoṇāsana is codified in photographic detail, and variations such as Parivṛtta Trikoṇāsana (Revolved Triangle) and Baddha Trikoṇāsana (Bound Triangle) evolved as extensions of this foundational form.

The Poetics of the Triangle

Among all geometric forms, the triangle is the most stable – three points define a plane. A tripod never wobbles. In Trikoṇāsana, we become that form: rooted through the feet, extended through the spine, and reaching in opposite directions. The posture anchors us to the earth and lifts us toward the sky – we are both grounded and spacious.

- One leg presses into the ground: stability.

- The other leg stretches outward: expansion.

- One arm lifts to the heavens: aspiration.

This pose teaches us to inhabit paradox – to be strong yet soft, firm yet fluid, aligned yet ever unfolding. We become a living Yantra, a sacred diagram made of body, breath, and intention.

Across spiritual traditions:

- The upright triangle is a symbol of fire – the rising flame of spiritual awakening.

- In yoga, it can represent the Tristhāna of Ashtanga Yoga: body, breath, and gaze.

- Or the eternal cycle of birth, life, and dissolution.

- Or the triad of sat–cit–ānanda – truth, consciousness, and bliss.

The upward-pointing triangle is the fire altar; the downward-pointing triangle is the sacred vessel. When they merge, they form the Star of Creation – the meeting of Śiva and Śakti, consciousness and energy, stillness and movement.

Some tantric texts teach that when the yogi holds Trikoṇāsana with unwavering steadiness, the three Guṇas come into dynamic balance. The posture becomes ritual – a silent offering to the divine that dwells in both form and formlessness.

Trikoṇāsana, then, is a myth in motion – a story of balance, of creative unfolding, and of return to the sacred center.

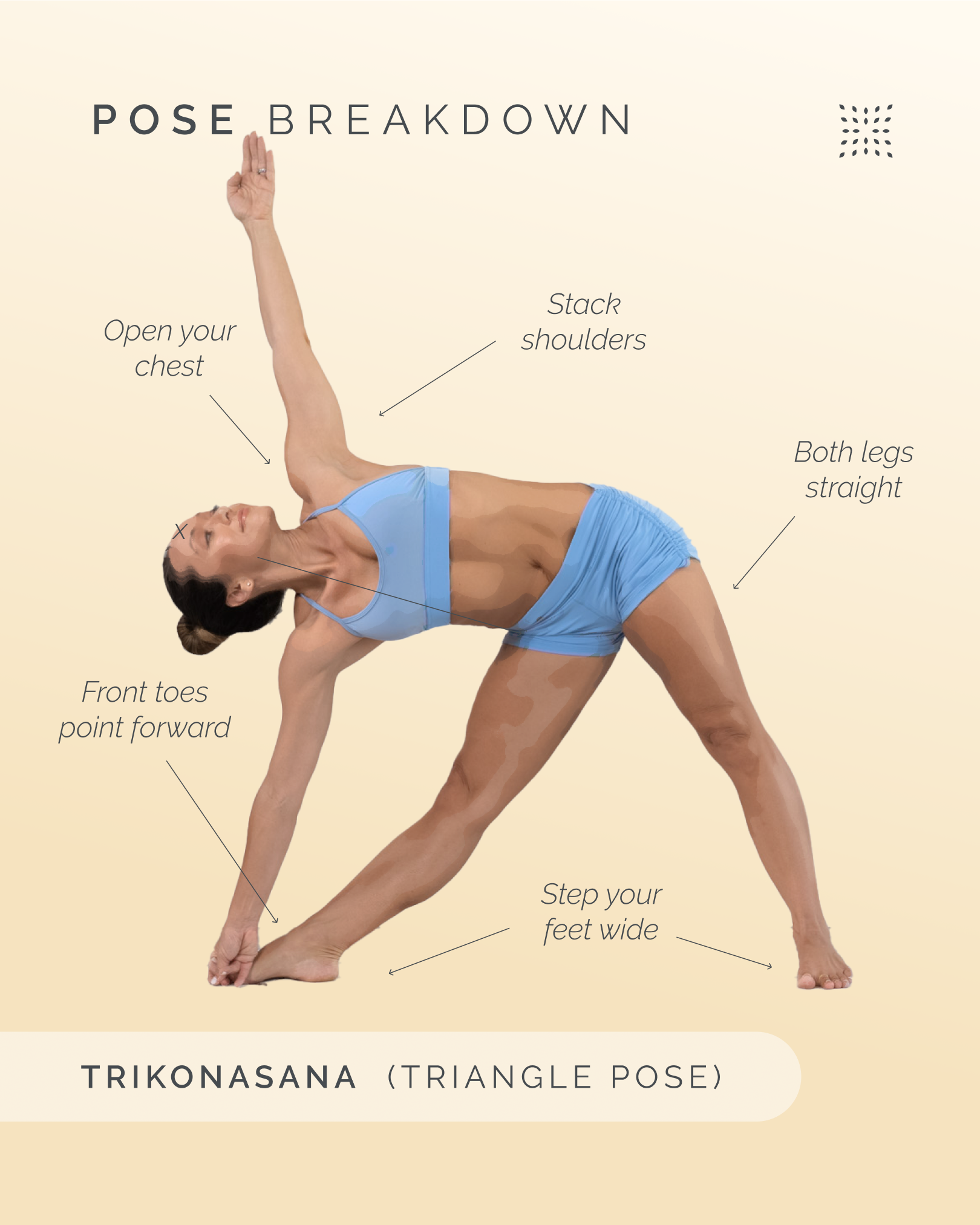

How to Practice Trikoṇāsana

Begin in Samasthitiḥ. On an inhalation, step the feet wide apart to the right. The distance between the feet determines the shape and stability of your triangle. Some schools of yoga teach a longer stance to emphasize stretch and openness; others recommend keeping the feet no wider than the length of your own leg to promote joint integrity and steadiness. As with any geometry lesson, there are many kinds of triangles – acute, obtuse, equilateral – and in yoga, each stance teaches something different. Explore what shape best suits your body and your practice.

In the Ashtanga Yoga method, the traditional guideline is to set the feet about the length of one leg apart. This slightly narrower stance helps maintain bandha, or internal energetic containment.

From here:

- Externally rotate the right hip and turn the right foot out 90 degrees.

- Align the back foot so that it either stays at a right angle or turns slightly inward, depending on the needs of your hips and knees.

- Line up the heels, or experiment with heel-to-arch alignment if balance feels shaky.

Press down through the big toe mounds. Engage the quadriceps and lift the kneecaps. Draw the femurs into the hip sockets. Activate the pelvic floor (Mūla Bandha) and draw the lower belly in toward the spine.

On an exhale, hinge at the right hip, extending the torso over the right leg. Reach the right arm toward the floor and the left arm to the sky. Keep the side body long and avoid collapsing into the lower ribs. The spine should feel spacious, not compressed.

- If available, clasp the right big toe with the right fingers and create gentle traction.

- If not, rest the hand on the shin, ankle, block, or chair – whatever supports integrity and breath.

Turn the gaze upward toward the left fingertips, if comfortable. Otherwise, keep the gaze neutral or downward. Stay for 5 deep breaths. To exit, press through the feet, rise on an inhale, and repeat on the left side.

Benefits of Trikoṇāsana

Physical & Anatomical

- Lengthens the side waist, spine, and intercostal muscles – deepening the breath.

- Improves spinal alignment and counteracts slumping or torsion.

- Builds strength in the legs and core (quads, hamstrings, glutes, obliques).

- Enhances postural awareness, especially in the thoracic spine and shoulders.

- Opens the hips, groins, and chest while improving balance and proprioception.

- Stimulates the abdominal organs (intestines, pancreas, kidneys), aiding digestion and detoxification.

Energetic & Subtle Body

- Activates Iḍā and Piṅgalā nāḍīs, balancing lunar and solar energies.

- Moves stuck Prāṇa-vāyu, especially through the torso and legs.

- Stimulates the Maṇipūra Chakra (solar plexus), awakening willpower and inner fire.

- Opens the Anāhata Chakra (heart center), cultivating compassion and spaciousness.

- Supports Ajñā Chakra (third eye) awareness when practiced with gaze and breath control.

- Trains the mind to stay centered between opposing actions — grounding and reaching.

- Can trigger a parasympathetic response, reducing anxiety and restoring calm.

Contraindications & Modifications

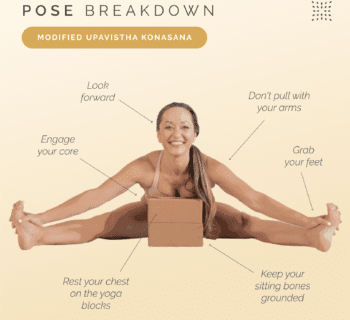

Lower Back or Disc Issues

- Risk: Lateral bending can compress sensitive discs.

- Modify: Use a block or elevate the hand; prioritize length in the spine over depth.

Neck or Cervical Spine Injury

- Risk: Gaze upward may strain the neck.

- Modify: Keep the head neutral or gaze downward.

Vertigo or Balance Disorders

- Risk: Wide stance and head turning may provoke dizziness.

- Modify: Practice with a wall or chair, and keep gaze neutral.

Want to explore how Trikoṇāsana feels in your own body? Practice with us on Omstars!

Accessibility for Trikoṇāsana

Utthita Trikonāsana

How to Modify Trikoṇāsana