When I first began practicing yoga, strength did not come naturally to me.

Flexibility, perhaps—but not the kind of inner steadiness that reveals itself in moments of muscular challenge and mental resolve. I still remember my very first led class with my teachers from India. Among all the poses we moved through, Navāsana—Boat Pose—was one of many that truly humbled me. As we lifted our legs and extended our arms, poised like boats suspended in midair, I didn’t feel like I was sailing. I felt like I was sinking.

There was something almost mischievous, yet profoundly kind, in the way my teachers would call out “Navāsana”—a gleam in their eyes, a smile curling at the edge of their lips, as if they knew exactly how much effort it would take. And yet, there was no harshness, no pushing. Just a quiet invitation to rise—to meet the fire of the pose with breath, to meet effort with presence. I never once felt shamed for trembling. Instead, I felt seen—encouraged to discover a strength I didn’t yet know I possessed.

To this day, when I practice Navāsana on my own, I hear their voices. I feel their subtle presence beside me, offering not commands, but a kind of steady faith: “You can stay. You can lift. You are stronger than you think.” And so, every time I lift into that familiar V-shape, I return not just to the posture, but to a moment in time when I first learned what it meant to float—not by force, but by trust.

Among the many shapes the yogi’s body takes on the mat, few are as deceptively simple and symbolically charged as Navāsana—Boat Pose. At first glance, it appears modest: a V-shape formed by lifting the legs and chest, balanced near the sitting bones. But within that suspended silhouette lies a confluence of ancient symbolism, modern anatomy, spiritual metaphor, and transformative potential.

Navāsana is not one of the poses found in the medieval haṭha yoga texts like the Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā or Gheraṇḍa Saṁhitā. It belongs to a later emergence—the early 20th-century revival of postural yoga led by T. Krishnamacharya and his students in Mysore. Though the form may have older cultural echoes, the pose itself does not appear by name or visual description in classical yogic scriptures. Instead, some yoga historians have suggested that Navāsana is part of the evolving synthesis of Indian spirituality with Western physical culture. Gymnastics, calisthenics, and core drills were already circulating in India at the time of the Mysore palace yoga experiments, and some suggest that it is within that cultural churning that Navāsana most likely arose—floating between tradition and innovation.

Yet even without direct scriptural reference, the metaphor of the boat is deeply embedded in Indic thought. In the Upaniṣads and the Bhagavad Gītā, the boat is invoked as a symbol of liberation from saṁsāra, the turbulent ocean of worldly existence. In Gītā 4.36, Krishna says, “You shall cross over all sin by the boat of knowledge.” The boat is the means by which we cross—the guru, the practice, the śāstra, all becoming vessels toward the far shore of mokṣa. In this light, Navāsana is not just a posture; it is a ritual reenactment of that spiritual crossing, enacted through the body.

Sanskrit Etymology: Sitting in the Boat

The name Navāsana (नवासन) breaks down into two parts:

- Nava (नव): “Boat,” derived from the root √nū/nav, meaning “to float, to navigate.”

- Āsana (आसन): “Seat” or “posture,” from the root √ās, meaning “to sit, dwell, abide.”

Thus, Navāsana means “the posture of the boat” or “seated as a boat.” But etymology alone does not capture its depth. In the pose, the practitioner becomes the boat—not as something that passively floats, but as something that navigates effort, breath, and balance. The body, breath, and mind must coordinate to remain afloat—not only physically, but metaphorically, in the inner waters of uncertainty, fatigue, and transformation.

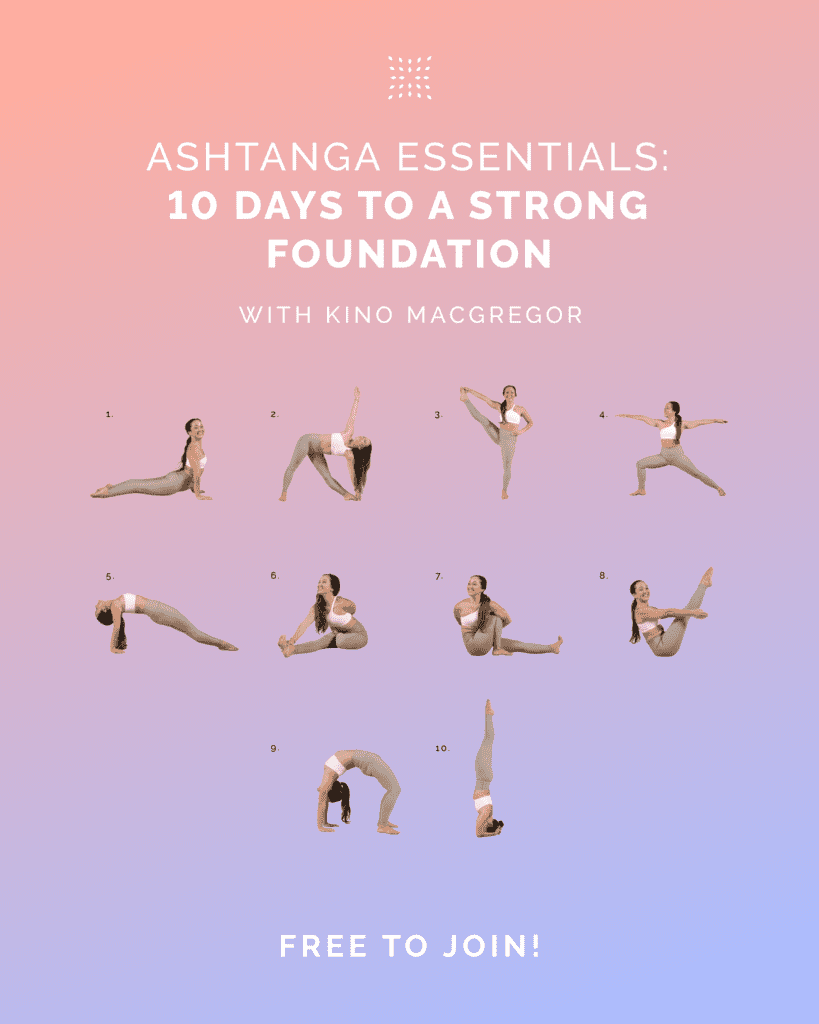

From Lineage to Lineage: Navāsana Across Yoga Styles

In Ashtanga Yoga, Navāsana holds a central place in the Primary Series (Yoga Chikitsā), where it appears just before the arm balance Bhujapīḍāsana and before the deep forward bends of Supta Koṇāsana and Kurmāsana. It is performed in five repetitions, each followed by a lift up—making it not only a test of strength but of breath and endurance. The spine is ideally lifted and long from the navel and upwards, legs extended and elevated, the arms reaching forward without gripping and the pelvis very gently tucked. The practitioner suspends the body in space with the subtle engagement of bandhas, especially uddīyāna bandha (abdominal lock) and mūla bandha (pelvic floor lift), while maintaining steady breath. In this system, Navāsana is as much an energetic experience as it is a muscular one.

In Vinyasa Flow and modern hybrid yoga, Navāsana is frequently used as a core-strengthening drill, often repurposed into sequences, pulses, or held isometrically for longer durations.

Iyengar Yoga offers a more therapeutic and structurally refined take. Props such as belts or bolsters may be used to support the spine or feet, ensuring that the shape supports spinal neutrality and hip alignment. The focus is on precision, alignment, and stability, with the goal of teaching the body how to access the core without strain. Each movement is broken down sequentially, allowing for safe, supported progression.

In contrast, Pilates presents an intriguing parallel. The Teaser is a near-identical shape to Navāsana, but arises from a different methodology. In Pilates, the Teaser is executed through controlled spinal articulation from a supine position, with a heavy emphasis on the “powerhouse”—a term referring to the coordinated engagement of the transverse abdominis, pelvic floor, diaphragm, and multifidus. Breath is synchronized but subtle, and the movement is part of a larger flow of neuromuscular control and spinal sequencing. Whereas in yoga, the breath may be made audible to enhance prāṇic flow, in Pilates the breath is quiet, intentional, and linked to precision of movement.

Western Anatomy and Alignment Insights

Anatomically, Navāsana is a full-body pose disguised as a core exercise. It engages the psoas major, iliacus, rectus abdominis, internal and external obliques, transverse abdominis, quadriceps, and spinal extensors, while requiring the paraspinals to isometrically stabilize. The hip flexors bear the brunt of the lifting action, especially in students with weak lower abdominals, often leading to over-recruitment of the psoas and compression of the lumbar spine.

Ideal alignment calls for a neutral or very gently tucked pelvis, lifted chest, and elongated spine—neither collapsing into kyphosis nor overextending into lumbar lordosis. The inner thighs draw toward one another, feet are active, and the arms reach forward without strain in the traps or shoulders. Scapular stabilization is essential, as is mindful engagement of the lower abdominal wall, not through clenching, but through subtle toning and breath-based integration.

Benefits: Core, Centering, and Crossing Over

When practiced with integrity, Navāsana offers a host of physical and energetic benefits. It strengthens the core musculature, builds postural awareness, and improves balance and coordination. Energetically, it awakens the manipūra chakra, located at the navel center—associated with fire, will, transformation, and self-discipline (tapas). It teaches the practitioner to hold steady in discomfort, to cultivate inner lift rather than collapse, and to engage breath, bandha, and mental focus in harmony.

Psychologically, Navāsana evokes a feeling of resilience. It is a pose that offers no crutches; it requires one to face gravity directly, to meet the middle of the body with intelligence and care. The image of the boat becomes a lived metaphor: Can you stay afloat? Can you navigate discomfort without losing your breath, your gaze, or your center?

Contraindications and Compassionate Adaptation

Despite its strength-building appeal, Navāsana is not for every body in its classical form. Those with low back pain, lumbar disc issues, SI joint instability, or sciatic nerve irritation may find the pose exacerbating. If the hip flexors dominate without sufficient support from the deep core or if the legs are lifted too high, the psoas pulls on the lumbar spine, risking compression and fatigue.

In postpartum bodies or students with diastasis recti, the intra-abdominal pressure may worsen abdominal separation, especially if the belly bulges outward or the breath is forced. Similarly, students with pelvic floor dysfunction may inadvertently bear down into the pelvic organs if the pose is held with tension rather than tone.

Breath-holding is another common pitfall. In an effort to “muscle through,” students often lock the breath, overriding the diaphragm and disrupting the balance of nervous system regulation. This is especially counterproductive for students with anxiety or trauma histories, where the shape of the pose may feel exposing or triggering.

Adaptations—such as bent knees, hands behind thighs, seated supine versions, or even visualization—can make the pose therapeutic rather than threatening. What matters most is not how high the legs lift, but how deeply the practitioner stays connected to breath, awareness, and support.

Conclusion: The Boat as a Path, Not a Performance

In every spiritual tradition, the boat is not just a mode of transport—it is a metaphor for transformation. In yoga, Navāsana is the boat, the body is the vessel, and the breath is the current. You are not merely building abs; you are training the nervous system to hold center in motion. You are teaching the mind to stay clear in effort. You are learning, breath by breath, to cross over the ocean of yourself.

So when you lift into Navāsana, remember: this is not a test, it is a crossing. Not a performance, but a passage. Not just a pose—but a prayer to stay afloat amidst stormy seas.