By Kino MacGregor

The name Sarvāṅgāsana speaks its intention plainly. Sarva means “all” or “entire.” Aṅga is “limb” or “part.” Āsana is the “seat,” the posture of presence. When joined, Sarvāṅgāsana becomes “the posture of all limbs.” It suggests more than an acrobatic arrangement. It points toward unanimity, toward a felt sense that the body for a time gathers into one field. When we add Salamba -“supported” – we are instructed on the method: supported posture of the whole body.

Although the word Sarvāṅgāsana is a modern term, the gesture of inversion runs deep in the yoga tradition. Medieval Haṭha texts describe Viparīta Karaṇī Mudrā, the “reversed action,” a practice in which the yogin inverts the body to preserve vitality and slow the leak of amṛta, the nectar of life. The Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā proclaims that by reversing the habitual flow, the downward seep of nectar is arrested, and decay is slowed. The imagery is poetic, but it conveys an energetic truth that practitioners still feel today: when you turn upside down, the usual direction of energy changes. You are no longer carried downstream by gravity but held in a current that lifts and restores.

By the twentieth century, as yoga moved into new forms of pedagogy, this older idea of “reversing the flow” took on a more defined physical expression. Krishnamacharya’s Yoga Makaranda includes shoulderstand as a principal inversion alongside headstand. B. K. S. Iyengar in Light on Yoga famously called it “the Mother of asanas,” not as sentiment but as physiology, for its harmonizing influence over nerves, circulation, and breath. Swami Sivananda enshrined it in his twelve basic postures, taught immediately after headstand as a balancing counterpart. In Aṣṭāṅga Vinyāsa Yoga, Sarvāṅgāsana is woven into the finishing sequence, sequenced with Halāsana, Karṇapīḍāsana, Piṇḍāsana, and Matsyāsana, creating a meditative arc that gently cools the fire of primary series before rest. Each lineage threads the same needle differently, but the fabric is shared: Sarvāṅgāsana is a posture of reversal, collection, and balance.

Benefits Across Time

The classical accounts sing in metaphor. Viparīta Karaṇī was said to prevent old age, to make the body luminous, to conserve the nectar that drips from the head. Such language does not need to be read literally to be true. It describes an inner physiology of attention: what usually runs outward is conserved inward, what usually scatters is gathered. Iyengar extended this poetry into pedagogy, writing that the pose “tones up the nervous system, invigorates the abdominal organs, and relieves one from fatigue.” The Sivananda tradition simply declares it “a boon to humanity,” balancing the endocrine system and calming the brain.

Contemporary science, though more clinical, has begun to glimpse the same pattern. Inversion increases venous return and stimulates the baroreceptors in the carotid sinus, shifting the autonomic nervous system toward parasympathetic dominance. Studies on yoga that include inverted postures report improvements in heart rate variability, a measure of vagal tone and resilience to stress. The lived account of students, quieter breath, calmer pulse, steadier mind, is echoed in this data. Even if the studies are modest in scope, the physiology resonates with what yogis have always known: shoulder stand is less about muscular power and more about the quieting of the nervous system.

Yet inversion carries its cautions. Research shows that intraocular pressure rises significantly in head-below-heart positions. For students with glaucoma, ocular hypertension, or retinal conditions, shoulder stand and similar inversions can pose risk. Cervical compression is another concern, particularly without support. Iyengar’s solution, folded blankets under the shoulders, head on the floor, remains one of the most intelligent adaptations in modern Asana. Medical literature also lists uncontrolled hypertension, hernia, cardiovascular disease, and cervical spondylosis as contraindications. Many traditions also advise refraining during menstruation, though opinions differ. Here, discernment and individualization matter more than dogma. The art is to deliver the essence of the pose safely, even if the form must change.

The Subtle Body

If the gross body teaches through nerves and vessels, the subtle body whispers through seals and centers. In Sarvāṅgāsana, Jālandhara bandha arises naturally as the chest lifts to meet the chin. This throat seal is said to “dam” the upward flow of prāṇa, preventing dissipation and allowing attention to pool in the heart. Haṭha texts describe it as a way of preserving the lunar nectar from the head, preventing it from being consumed by the solar fire in the belly. In subtle body language, the inversion awakens Viśuddha chakra, the center of purification and expression. The felt effect is quiet: the palate widens, the tongue softens, the exhale grows longer. For a few breaths, everything feels organized into one continuum. The name Sarvāṅga – “all limbs” – becomes experiential rather than conceptual.

Technique and Alignment

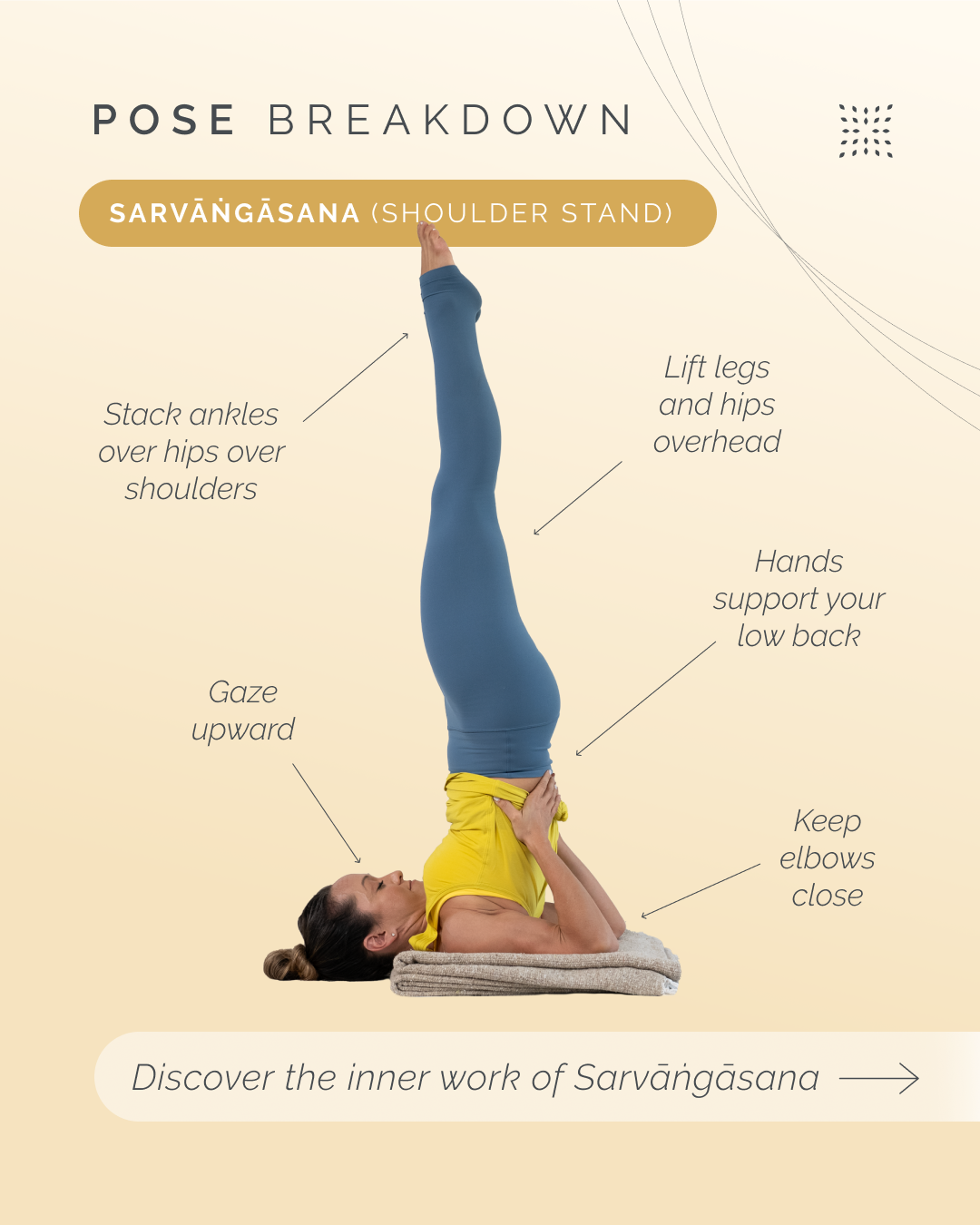

The entry matters as much as the posture itself. From a supine position, roll the shoulders back onto a firm base, often a stack of folded blankets, so the cervical spine is free from load. Bring the legs overhead into Halāsana first, hands supporting the back ribs. Walk the hands higher until the chest lifts, then send the legs to vertical. Let the sternum rise to the chin rather than the chin pressing down. Keep the throat soft, eyes steady, and the breath calm. The weight belongs on the backs of the shoulders and upper arms, never on the neck.

Exiting is just as deliberate. Lower the legs back into Halāsana, release the hands, and slowly roll the spine down with control. In Aṣṭāṅga, the sequence carries forward into Piṇḍāsana and Matsyāsana, which counterbalance the inversion by opening the chest. In Iyengar practice, one might linger in Sarvāṅgāsana for several minutes, then return through Plough and rest in Śavāsana, or move into Matsyāsana to release the throat. In Sivananda’s classical sequence, Shoulder stand flows into Plough, Fish, and finally relaxation. Each tradition follows its own rhythm, but all share the alignment principle: lift the chest, support the neck, and let the breath govern the duration.

The Heart of the Pose

The question that threads through history, physiology, subtle body, and technique is simple: why invert? The classical yogins answered in metaphor: to reverse the downward seep of nectar. Modern teachers answered in physiology: to regulate nerves and glands. Scientists answer in data: to shift the body toward calm parasympathetic balance. Yet behind all these explanations lies the experience itself. When the world is upside down, for a brief time the mind is quiet. The pulse steadies. The limbs feel as though they belong to one body rather than many parts.

This is where your own story as a teacher or practitioner enters. Perhaps it is the first time you felt the chest rise effortlessly and realized you were truly standing on your shoulders, not your neck. Or the memory of a Mysore room in Mysore or Miami, when the collective breath carried the finishing sequence into silence. Or perhaps the softer story, the one that lives in students who cannot invert fully but find the same nectar in legs-up-the-wall, in a gentle supported variation where the heart rests.

Sarvāṅgāsana, the posture of all limbs, is not about contortion or perfection. It is about gathering what scatters, reversing what leaks away, and remembering that wholeness is possible in the body, if only for a few breaths at a time.

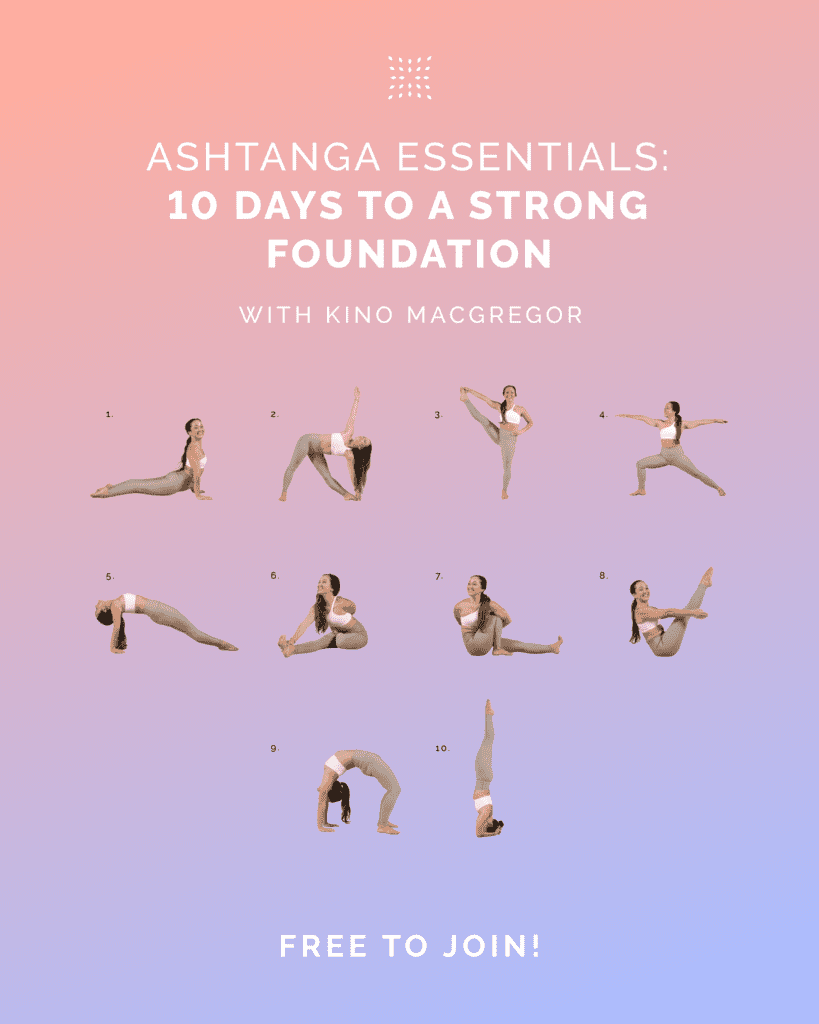

Want to explore Sarvāṅgāsana and other classical postures in depth? Try this yoga pose tutorial with Kino!