The word Daṇḍāsana (दण्डासन) is composed of two Sanskrit terms: daṇḍa, meaning “staff,” “rod,” or “stick,” and āsana, “seat” or “established posture.”

The root of daṇḍa appears throughout Indian philosophical and scriptural literature. In the Ṛg Veda, it denotes the staff as a symbol of authority and alignment, the implement of both power and righteousness. In the Manusmṛti, daṇḍa is not only the physical staff held by the king but also the cosmic principle of justice, daṇḍa-nīti, the discipline of law that maintains harmony in the world. The staff stands upright, perfectly balanced between heaven and earth. It becomes the emblem of integrity, the moral and physical axis around which all action should align.

In yogic and ascetic traditions, the staff has equally sacred associations. The daṇḍin, or staff-bearer, is the archetype of the renunciant who has renounced worldly attachments and walks with the support of a single stick, a symbol of steadiness, self-support, and ascetic discipline. The Śaiva ascetic carries a daṇḍa as a sign of mastery over the body and mind, while the ekadaṇḍin renunciant of the Advaita Vedānta order uses it to mark a life lived in singular focus on Brahman. In each case, the staff represents that which does not waver. When we practice Daṇḍāsana, we align ourselves with this lineage of steadiness. The spine becomes the living staff, the inner Meru, the mountain axis around which all experience revolves.

In the earliest textual references to āsana, such as Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra 2.46 – “sthira-sukham āsanam” – the term refers to a seated, stable posture suitable for meditation. Daṇḍāsana thus echoes the spirit of those earliest seats. It is the ground of all seated positions, the posture from which forward bends, twists, and hip openers arise. In this sense, Daṇḍāsana is much like the seated version of Samasthitiḥ. Where Samasthitiḥ is the standing posture of equilibrium at the start of the sūrya namaskāra, Daṇḍāsana is its seated reflection: the mind centered, the limbs balanced, the vertical and horizontal planes in harmony.

Historically, Daṇḍāsana as a named posture does not appear in the early haṭha yoga manuals such as the Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā or Gheraṇḍa Saṃhitā in the detailed lists of postures, though the geometry of the staff is implicit in many meditative seats. Its presence becomes formalized in the twentieth-century codifications of āsana, where teachers like Sri T. Krishnamacharya, and later B. K. S. Iyengar and K. Pattabhi Jois, articulated Daṇḍāsana as the foundational sitting pose.

Daṇḍāsana in Different Yoga Traditions

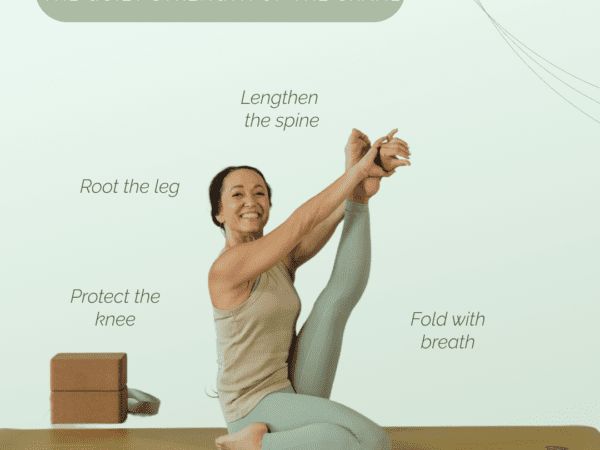

In the Ashtanga Yoga tradition, interestingly, Daṇḍāsana is not listed among the primary or intermediate postures of the vinyāsa system. It appears rather as a moment, the brief, precise alignment one arrives in when performing the “jump through” from Adho Mukha Śvānāsana to a seated position. In this transition, the practitioner lifts the body, crosses or extends the legs, and lands with them outstretched, heels pressing down, spine upright, fingers beside the hips. It is a fleeting stillness between movements, a pause that prepares the field for the next posture. Every Ashtanga Yoga practitioner who has joined a Led class will remember hearing the phrase “jump through, straight legs, sit down”. This refers to the pause held in Daṇḍāsana before entering or preparing for the next pose. In the Primary Series, the pause held in Daṇḍāsana is marked by five breaths before Paschimattanasana, even though it remains unnamed. In all remaining poses that pause in Daṇḍāsana, it is either a single breath or a pause between breaths. Later, in the advanced series, especially in the Fourth and Fifth series, the term Daṇḍāsana reappears as part of elaborate sequences such as Bhuja Daṇḍāsana, Yoga Daṇḍāsana, Adho Mukha Daṇḍāsana, and others. Each of these advanced variations elaborates on the same principle: an unwavering axis as the staff of consciousness.

In Iyengar Yoga, Daṇḍāsana is treated with the seriousness of a standing pose. It is not a simple resting position but an act of deep alignment. The legs are extended and actively engaged, the thighs firm, kneecaps lifted, heels pressing into the ground. The spine rises from the pelvis like a temple pillar, the chest broad, shoulders back, gaze soft. Iyengar often compared the pose to a “staff of light,” the body’s energy channeling upward from the earth. Props — such as a belt around the thighs or blocks beneath the hands, are used to teach the subtle activation of muscles that create lift through the spine. The alignment in Daṇḍāsana is said to awaken mūla bandha, the root lock, and cultivate both grounding and ascension.

In Haṭha Yoga, Ashtanga Yoga, and Iyengar Yoga, the concept of the staff appears in Caturaṅga Daṇḍāsana, the four-limbed staff pose, which links the sūrya namaskāra sequence. Here, the staff is horizontal rather than vertical. The spine, legs, and arms form one continuous line, supported by the strength of the core. The same inner principle applies: unwavering alignment. The term caturaṅga means “four-limbed,” indicating that the entire body serves as the staff. It is the active expression of Daṇḍāsana, steadiness in motion, the geometry of stillness turned kinetic.

In contemporary vinyāsa, Daṇḍāsana has often been overlooked, yet it remains the hidden key to many transitions. It teaches the neutral line of the spine that reappears in plank, in Chaturanga Daṇḍāsana, in the jump-throughs and jump-backs that punctuate the vinyāsa rhythm. When practiced with awareness, it reveals how strength and softness interlace. The firmness of the thighs, the rootedness of the hands, and the lift of the sternum all mirror the dynamic balance required in more complex poses.

Technique

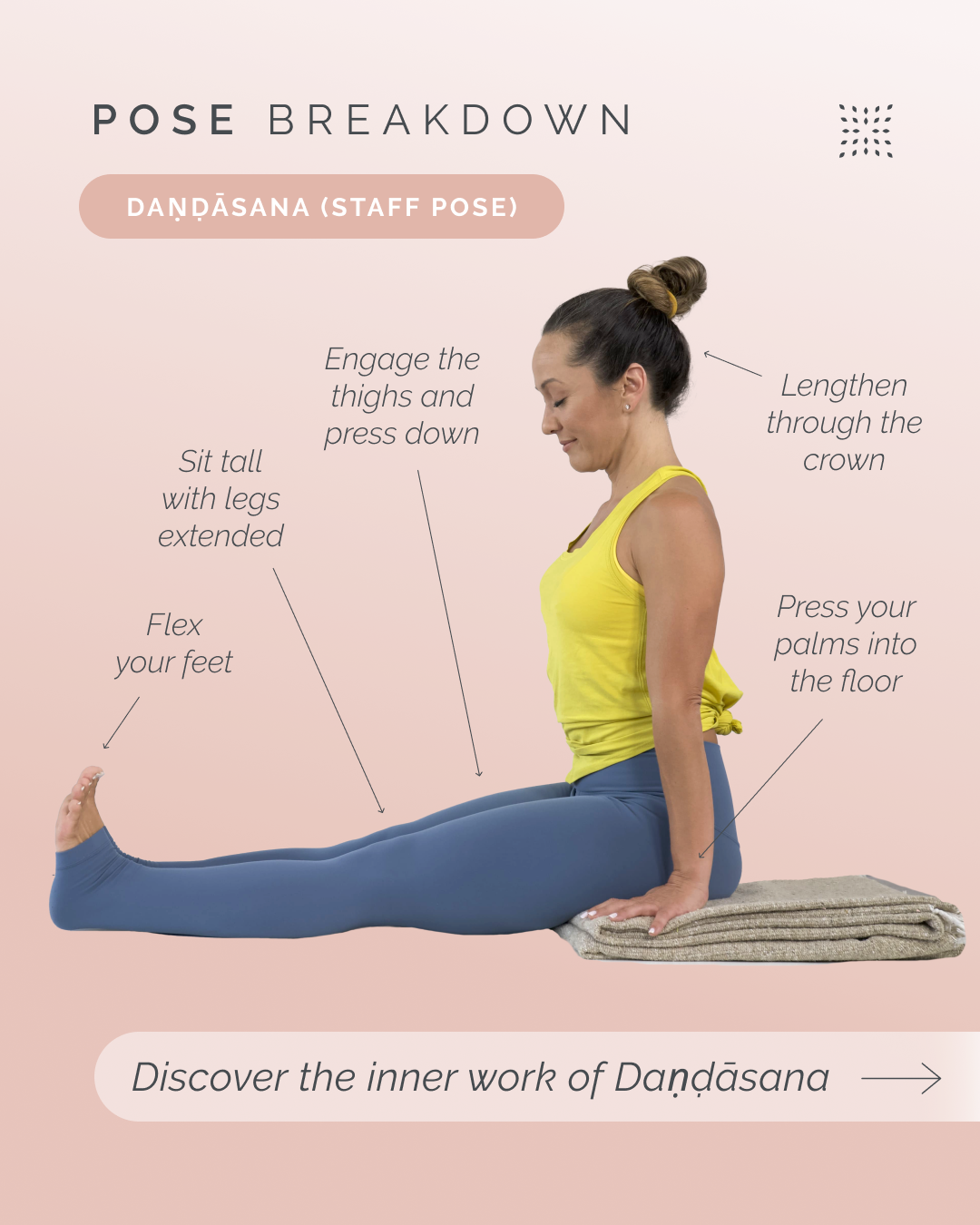

To come into Daṇḍāsana, one sits with both legs extended straight forward, the toes active, the inner thighs with just a hint of slightly inward rotation that comes from the bases of the big toes pressing together. The sitting bones ground into the earth, while the spine lengthens upward. The natural curvature of the spine is expressed with the lumbar curve and a lifted thoracic spine. The crown of the head reaches toward the sky, the gaze softly forward at the horizon. The palms press lightly beside the hips, fingers facing forward, arms straight without locking the elbows while allowing variation for arm length. The shoulders draw down the back and the neck remains free. The chest expands with each breath, such that the sternum rises up towards the gently tucked chin and the breath itself flows evenly, neither forced nor shallow. In this alignment, the body forms a staff: rooted, steady, luminous.

The energetic dimension of the pose is subtle yet profound. The central channel, Suṣumṇā nāḍī, is imagined to run through the spine from mūlādhāra at the pelvic floor to Sahasrāra at the crown. In Daṇḍāsana, this channel is unobstructed. The earth element grounds the lower body, while the upward movement of prāṇa rises freely. The pose thus becomes a preparation for meditation, establishing the equilibrium between prāṇa and Apāna, the ascending and descending currents. It is both a measure of physical alignment and a mirror of inner order.

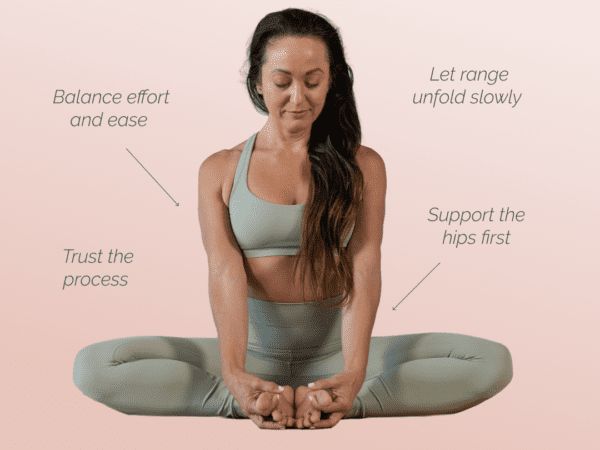

Practiced regularly, Daṇḍāsana refines proprioception and strengthens the back and abdominal muscles that support posture. It awakens the hamstrings and lengthens the calves, improving circulation through the legs. It teaches how to sit upright without rigidity and how to balance effort with ease. For those who spend long hours seated in chairs or crouched over devices, the pose serves as an antidote, a way to rediscover the natural architecture of the spine.

At the same time, Daṇḍāsana offers a psychological lesson. To sit upright, grounded yet alert, is to embody dignity. It calls forth the inner authority that the word daṇḍa originally signified. The practitioner becomes both king and ascetic, holding the invisible staff of self-mastery. This alignment generates clarity of mind, steadiness of purpose, and a felt connection to something vertical and transcendent within the human form.

Like all āsanas, Daṇḍāsana also has its contraindications. Those with severe lower-back or hamstring injuries must approach it gently, sitting on a folded blanket to tilt the pelvis forward and avoid strain. Tightness in the hip flexors or weakness in the back can cause rounding of the spine, which dulls the energetic effect of the pose. Support under the hands or hips, or slight bending of the knees, can help maintain the integrity of the line. The goal is never external perfection but internal coherence, the felt sense of the staff of energy rising unobstructed through the body. Additionally, some students may find it inaccessible to touch the bases of the big toes together, in which case, the activation of the legs remains and the direction given is to engage the feet such that the heel rests between the base of the big toe and the base of the little toe.

Final Reflection Points

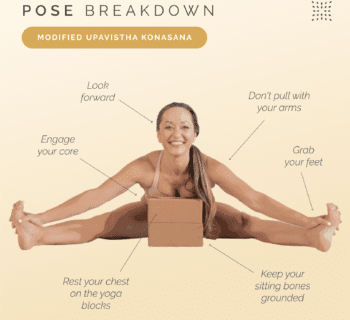

Seen through the wider lens of yoga philosophy, Daṇḍāsana represents the meeting of opposites. The vertical lift of the spine meets the horizontal spread of the legs, creating a cross of energies. The pose teaches how to be firm without hardness, extended without dispersal. It becomes a metaphor for spiritual life: rooted in the earth yet reaching toward the infinite.

The ancient seers spoke of the human being as a miniature cosmos, with the spine as Mount Meru, the world-axis connecting the realms of heaven, earth, and the underworld. In Daṇḍāsana, we sit upon this mountain. The body becomes a pillar between the visible and invisible worlds. The breath, rising and falling, carves inner pathways through which consciousness ascends. To sit in Daṇḍāsana is to participate in that cosmic alignment, to remember that the same geometry that steadies a mountain or guides the flight of stars exists within the human frame.

Over time, this simple posture reveals itself as a profound meditation. The stillness cultivated here is not passive but alive, a radiant equilibrium. Each breath polishes the invisible staff of the spine until awareness shines unobstructed through it. The practitioner learns to trust in that inner axis, to stand tall within, even when seated.

Thus Daṇḍāsana, the staff pose, becomes the unspoken root of all practice. It is the measure of our alignment, the reminder of integrity. From it we fold forward into humility, twist toward discernment, and rise into backbends of courage. Each movement begins and ends at its base. It is seated Samasthitiḥ, the geometry of steadiness incarnate, a still point from which the journey of yoga both begins and eternally returns.

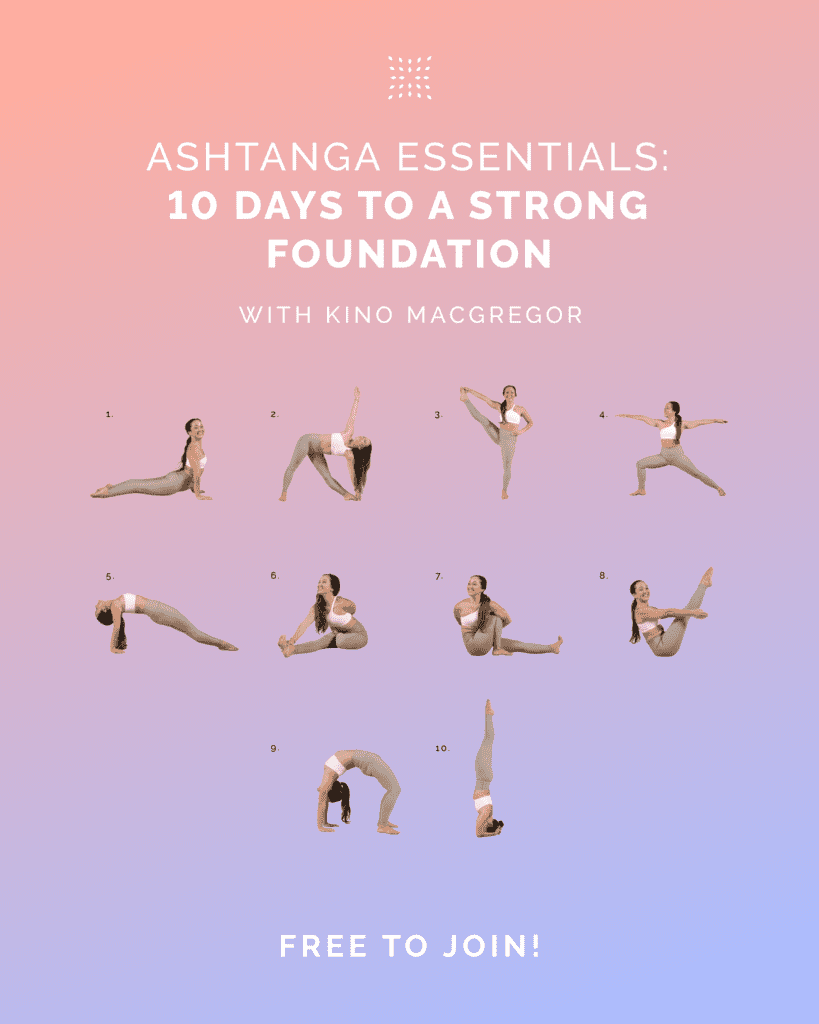

To embody the practice of Daṇḍāsana try this tutorial on Omstars!