Padāṅguṣṭhāsana is one of the most unassuming shapes in the Ashtanga Yoga method, yet it holds the quiet power of a first teaching.

The name joins pada, meaning foot, with aṅguṣṭha, meaning the great toe. Like many Sanskrit compounds, the word is simple on the surface and layered underneath. The “toe” in classical literature carries connotations of grounding, humility and beginning. The pāda is the base upon which all movement rises, and the aṅguṣṭha is the point through which the practitioner makes intimate contact with the earth. In the Gheraṇḍa Saṁhitā, forward folds such as paścimottānāsana are praised for calming the mind, cooling the nervous system and awakening inner fire.

Padāṅguṣṭhāsana does not appear by name in early texts, yet it belongs to the family of standing forward bends that deliver the same qualities of inwardness, clarity and purification. What is unique about this particular posture is the direct relationship between the toes and the fingers, a connection that becomes symbolic of yoga itself. Two ends of the body meet. Two ends of the self touch. The gross meets the subtle and something in between begins to open.

In the Ashtanga Yoga method, Padāṅguṣṭhāsana initiates the standing sequence.

The first forward fold from standing sets the tone for what follows. Gravity begins to guide the descent and the intelligence of the bandhas awakens in response. When the body folds forward from an upright position, the abdominal organs shift naturally out of the way. This makes room for the breath and gently invites the deeper structures of the pelvis to participate in the action of the fold. The legs take on the foundational work, creating the stability that allows subtle flexibility to emerge. As the quadriceps engage, their tone signals to the hamstrings that it is safe to lengthen. In this way strength and suppleness move together. The pose becomes a living conversation between the front and back body, between effort and release, between grounding and lifting.

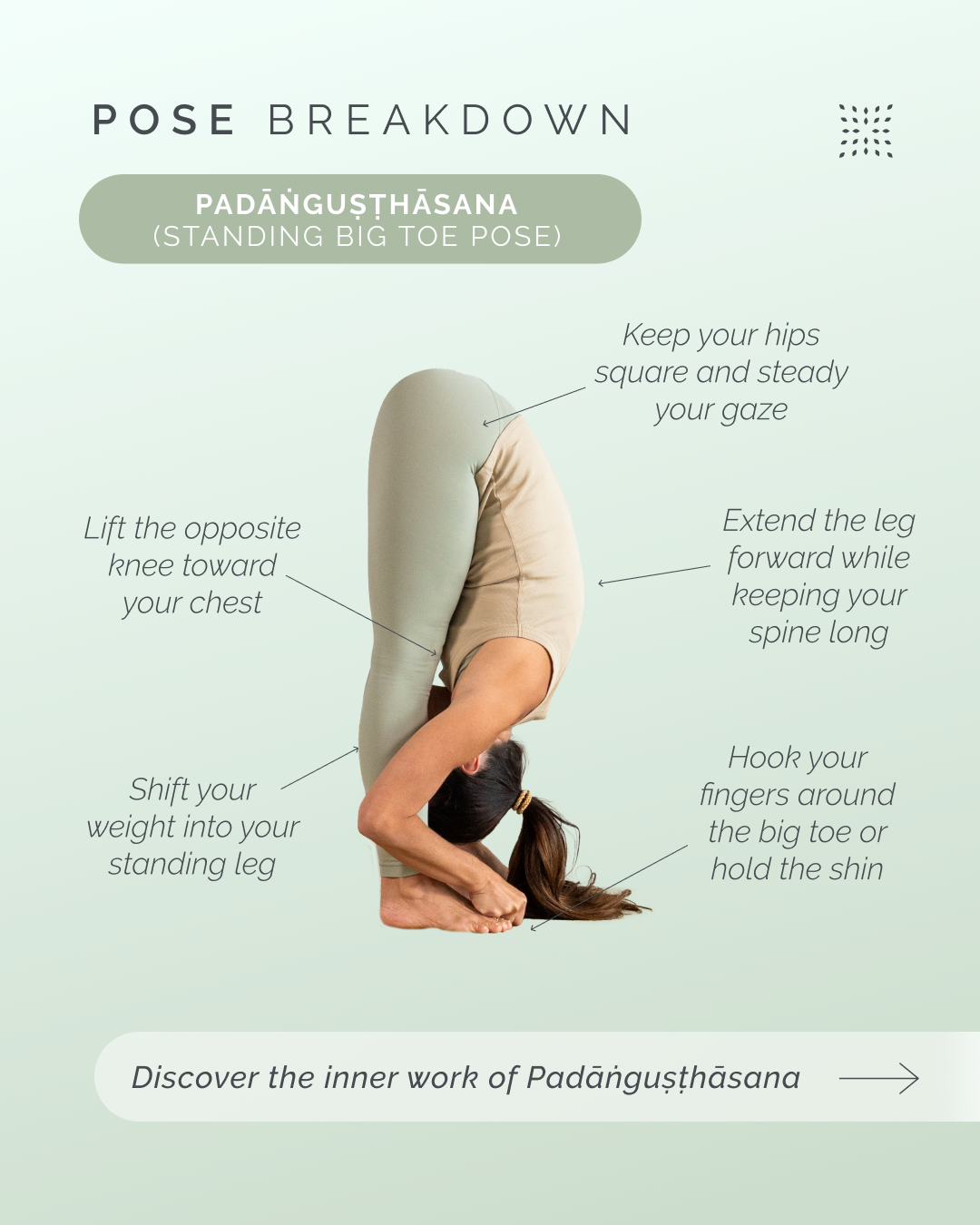

The physical gesture of Padāṅguṣṭhāsana is simple. The legs are straight, the first three fingers loop around the big toes and the elbows soften outward as the shoulder blades glide down the back.

Depth does not come by pulling. The wisdom of the posture blossoms when force gives way to thoughtful surrender. The chin draws slightly inward, the head hangs freely and the neck releases. The gaze moves toward the tip of the nose and the eyes remain open to keep awareness steady. The pelvis tips slightly forward so the weight can settle evenly through the center of the feet. If balance wavers, the answer is not in gripping the toes but in feeling into the center of gravity. The legs provide the support and the pelvis organizes itself around that central point.

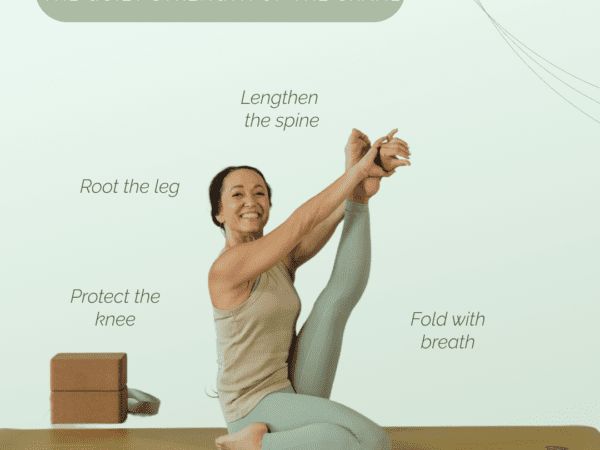

All forward folds contain a measure of spinal flexion.

They rely on the subtle activation of the front body to create space for the back body to lengthen. In the active version of Padāṅguṣṭhāsana, the culmination of the pose is held by a refined strength through the abdomen. Each breath becomes an invitation to fold a little deeper. The axis of the posture resides in the pelvis. As the practitioner pivots around the hip joints, the hinge of the hips reveals itself as a gateway. Once the natural limit of the hinge is met, the abdominal muscles draw inward and the ribs fold toward the thighs. Spinal flexion then becomes supported, intentional and safe.

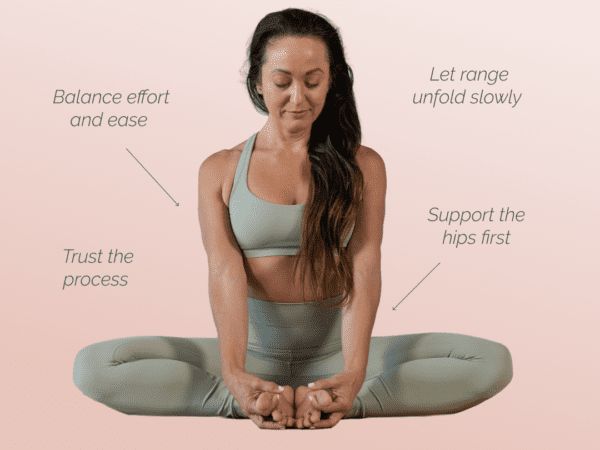

There is a second expression of this posture that many practitioners know as the ragdoll fold.

In this quieter variation the front body does not actively hold the shape. Gravity takes over and the torso drapes forward. This version can be soothing to the nervous system and helpful for those who struggle with tension in the back body. Yet it must be approached with discernment. Students with tenderness in the hamstring attachments may find prolonged passive stretches place too much weight on the delicate structures around the sitting bones. For these practitioners, shorter holds with mindful activation will be safer. For others, the passivity itself becomes a meditative release, softening the breath and calming the inner landscape.

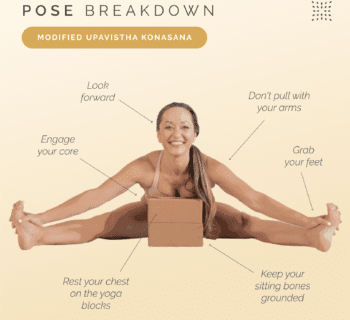

In the Iyengar Yoga tradition, Padāṅguṣṭhāsana takes on a more architectural precision.

The emphasis rests on alignment, stability and the awakening of conscious intelligence throughout the body. Props may be used for those who cannot comfortably reach the toes. Blocks under the hands can help maintain integrity in the spine and pelvis while the practitioner builds familiarity with the shape. The legs remain firm. The thighs spiral slightly inward and the kneecaps lift to ensure the quadriceps are fully awake. The sternum moves forward before it moves downward, which teaches students to hinge from the hip joints rather than collapse into the lower back. This interpretation highlights the spaciousness of the pose and can be particularly therapeutic for students who need to refine structural awareness or recover from injury.

Padāṅguṣṭhāsana carries many benefits. It lengthens the hamstrings, awakens the calves, and strengthens the quadriceps. It massages the abdominal organs as they draw inward. It quiets the nervous system and encourages introspection. It teaches humility. It invites the practitioner to bow, not in defeat but in reverence. Contraindications include active hamstring tears, acute lower back injuries or herniated discs. In such cases the pose may still be practiced but with a bent knee variation, gentle props or the guidance of an experienced teacher. Pregnancy may require modifications to account for increased laxity and shifting balance.

The deeper truth of Padāṅguṣṭhāsana reveals itself over time.

The standing forward fold is more than a stretch. It is an initiation into the subtle proprioception that will later guide the body into inversions. The same intelligence that draws the torso toward the legs creates the pathway for pike entries into handstand and other inverted shapes. Without understanding the forward fold as a felt experience, these transitions remain elusive. The pose becomes a study in directionality, teaching the practitioner to feel the line of energy moving from the center of the pelvis through the core and into the arms. In this way, Padāṅguṣṭhāsana becomes one of the earliest teachers of inversion mechanics.

Standing at the threshold of the Ashtanga sequence, Padāṅguṣṭhāsana whispers the first lesson.

Yoga begins where the earth meets the body and where humility meets effort. The big toe becomes a small doorway into a vast interior. The forward fold becomes a pilgrimage toward the quiet center within. And the breath becomes the link between the two. Each time the practitioner bows forward, the pose asks the same question. Are you willing to meet yourself where you already stand?

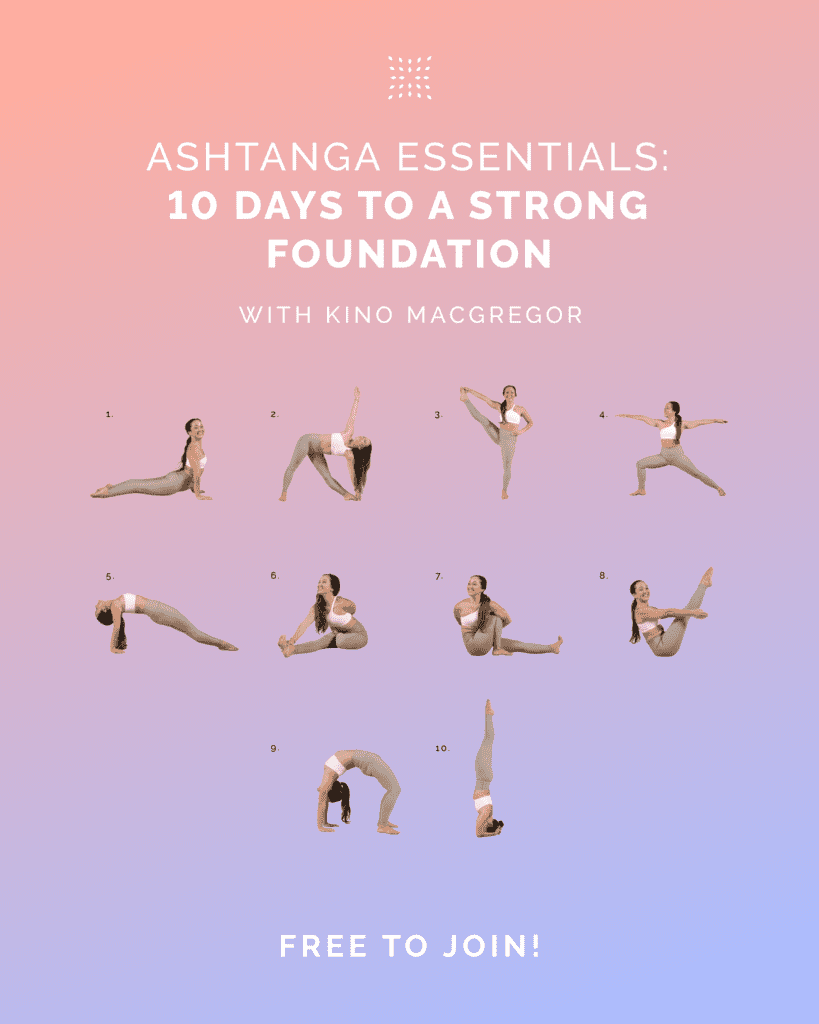

If you want to embody this posture in your own practice, explore the Padāṅguṣṭhāsana tutorial on Omstars, and this accessible variation version as well. You can also build your practice from the ground up with Ashtanga Yoga Building Blocks, a foundational series that supports strength, alignment, and consistency.