The Sanskrit name Prasārita Pādottānāsana unfolds its meaning with the elegance of the posture itself. Prasārita means “spread out” or “expanded,” from the root √sṛ meaning “to flow or spread.”

Pāda means “foot” or “leg,” and uttāna derives from ud (upward) and tan (to stretch), meaning “intense stretch” or “extended.” Together, the name evokes an image of the body as a horizon line; feet wide upon the earth, spine lengthened like a river meeting the sky, breath spreading in every direction.

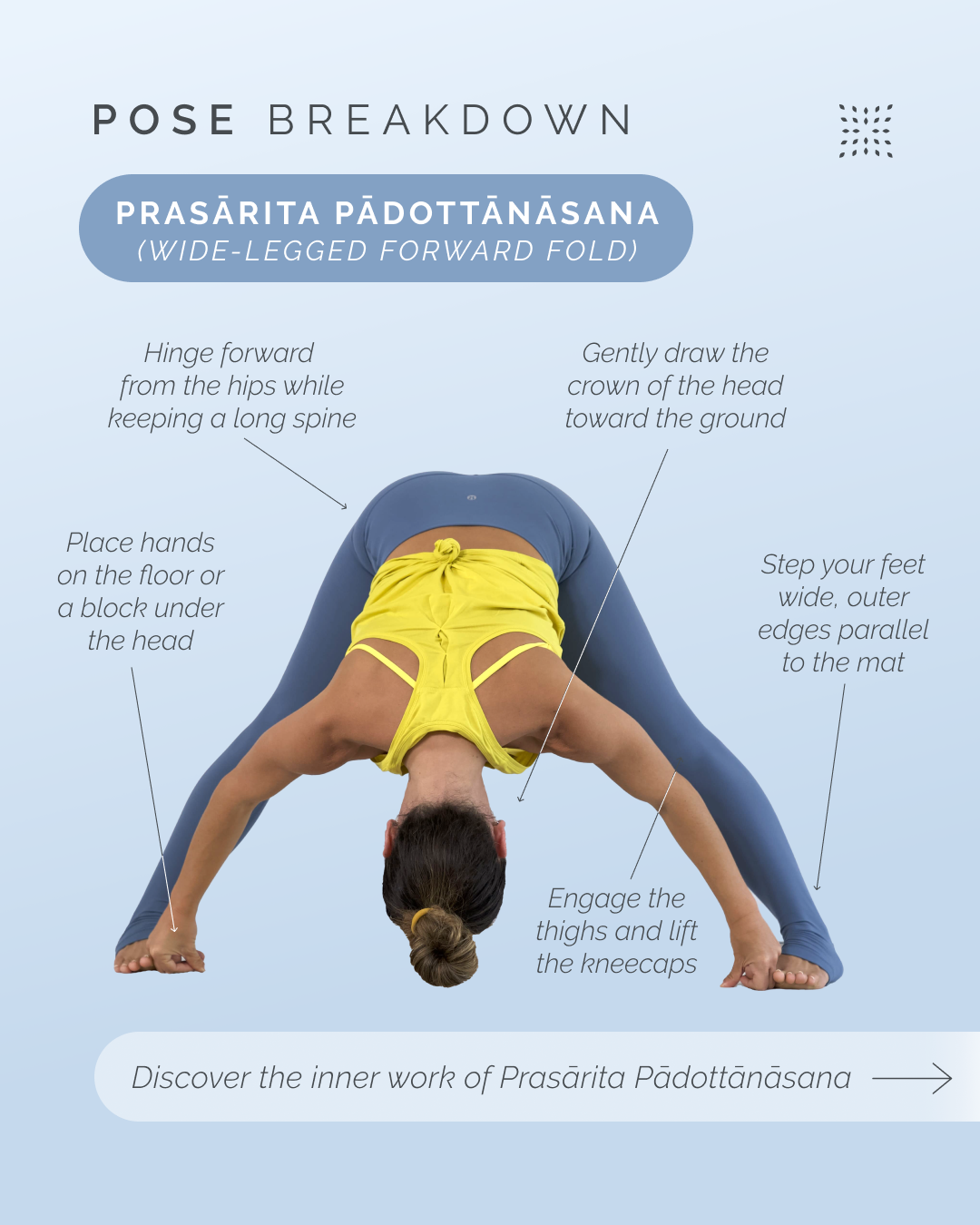

At first glance, this posture appears simple. The body folds forward, the legs form a strong base, the spine releases. Yet within that simplicity is a landscape of subtle dynamics. The pose draws upon the interplay of grounding and release, effort and surrender, strength and trust. The alignment cues serve as gateways to these inner dimensions. Standing with the feet wide, the outer edges parallel to the mat and the toes turned gently inward, the practitioner creates a sense of containment. The thighs engage and lift the kneecaps, the legs draw energetically toward each other, and the arches lift as if pulling the earth up through the bones. The ankles stabilize, and that stability travels upward into the pelvic floor, where the subtle musculature of mūla bandha begins to awaken. The lower belly tones, linking the work of the legs with the center of the body.

When folding forward, the movement originates not from collapse but from intelligence. The hinge at the hips is a gesture of clarity rather than force. The spine remains long, the heart reaching forward before the head descends. The crown of the head becomes an offering, drawing softly toward the ground as the breath steadies and deepens. This is a posture where gravity becomes a teacher. The surrender of the torso is not a collapse but an act of trust, a participation in the earth’s pull. The more one roots through the legs, the lighter the spine becomes.

The Ashtanga Yoga tradition preserves four classical variations of Prasārita Pādottānāsana.

In the first, the hands rest on the ground in line with the shoulders, grounding the posture and maintaining spinal length. In the second, the hands hold the waist, challenging the forward tilt and drawing the crown of the head toward the floor. In the third, the hands interlace behind the back, opening the chest and guiding the shoulders into an expression of internal rotation. The fourth returns to the central axis, with first three fingers of each hand wrapping around the big toes, the elbows pointed upwards, the crown of the head pointed towards the ground and an internal expression of equilibrium. Each variation carries its own psychological texture, stability, humility, openness, and balance.

In Iyengar Yoga, Prasārita Pādottānāsana becomes a study in alignment and precision.

The hands may rest on blocks, the head supported by a bolster or chair, emphasizing the elongation of the spine and the release of the neck. In Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā and other classical manuals, while this specific pose is not explicitly named, its spirit echoes in forward folds such as Pascimottānāsana, which represents the inward journey of consciousness. The wide-legged stance of Prasārita Pādottānāsana expands this principle, inviting the practitioner to find inward reflection not through contraction, but through spaciousness.

In more contemporary Vinyāsa traditions, this pose often serves as a moment of rest and integration between dynamic sequences. It bridges the standing and seated realms of the practice, a quiet transition where energy gathers inward. Its shape resonates with other postures that invite the torso to move deeply between the legs, such as Kurmasana (Tortoise Pose) and Tittibhasana (Firefly Pose). Both of those postures evolve from the same archetype: the withdrawal of the senses into the inner shell, the radiance of light emerging from the darkness within. In Prasārita Pādottānāsana, one can feel the prelude to this inner journey, the moment before the full retreat, when the practitioner still stands upon the earth but begins to move inward toward silence.

The mythology of the pose can be glimpsed through its gestures.

The downward movement of the head toward the earth recalls acts of humility: the devotee bowing before the altar, the sage offering knowledge, the goddess touching the soil that sustains all life. In this way, the pose becomes both devotional and cosmic, a posture of embodied reverence that links the heavens and the earth through the conduit of the spine.

For practitioners with sensitive hamstrings, sacroiliac issues, or conditions such as proximal hamstring tendinopathy (often colloquially called “yoga butt”), Prasārita Pādottānāsana requires gentleness and discernment. The key lies in the articulation of the hips and the engagement of the quadriceps to protect the back of the thighs. Props such as blocks beneath the hands or a chair under the head allow the forward fold to remain active yet supported. In yoga, there is no virtue in strain; the sukha, the quiet ease, must remain present even amid intensity.

To step wide in this posture is to make space, not only in the body but also in the mind. The wide-legged stance represents expansion, but the forward fold signifies introspection. Together, they reveal a paradox at the heart of yoga: through openness, one finds depth; through surrender, one discovers strength. When the crown of the head descends toward the ground, the world turns upside down for a moment, and the practitioner learns to see from another perspective.

There is a stillness unique to this shape, an echo of inner vastness. With each exhalation, the body softens toward the earth. With each inhalation, the inner horizon expands. The legs remain strong, the breath steady, the mind quiet. In this posture, one begins to understand that true expansion is not outward display but inward spaciousness.

This is a place in the practice where personal reflection belongs, a place to recall moments of humility, to meet oneself at the threshold between strength and surrender. The outer form is only the doorway; the real work begins when the mind follows the body inward, listening to what the silence beneath the breath has to teach.

Practice Prasārita Pādottānāsana on Omstars with Kino and embody proper technique and alignment with this pose tutorial.